welcome to our witness evidence wiki

This wiki catalogues empirical evidence relating to witness evidence and miscarriages of justice.

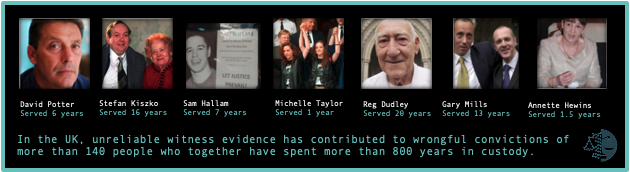

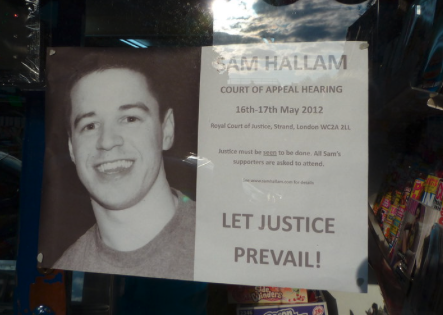

Witness Evidence Related Miscarriages of Justice in the UK

Illustrative cases from the UK

Papers

Please feel free to add any relevant papers to our reference of case lists using the ‘+ Add Paper’ button at the bottom of this table.

| Title | Author(s) | Year | Tag(s) | Link |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planting misinformation in the human mind: A 30-year investigation of the malleability of memory | Elizabeth Loftus | 2005 | Suggestion | View paper |

Witness evidence – research summary

Research provides insight that can help assess whether witness testimony is accurate. Witness testimony may be inaccurate because a witness is lying, or because a witness has a false memory. Research in psychology can provide some insight into factors associated with accurate and inaccurate memory that might help inform testimony evaluations. However, data suggests that jurors may have problems distinguishing accurate and inaccurate testimony, and that assumptions jurors rely on may differ from those shown to be important by scientific research. Thus, we can pinpoint potential cases in which decision-makers in the legal system might be particularly likely to make mistakes when interpreting witness testimony.

Deception

The Difficulty Detecting Deception

Research highlights the difficulty of detecting deception in witness testimony, and cues to deceit have been described as “faint and unreliable”. Meta-analyses suggest that people are correct in identifying whether a statement is the truth or a lie about 54% of the time.

Techniques to Detect Deception

Specific techniques have included:

(1) Physiological measures such as polygraphs (according to which those who are lying have a heightened stress response).

(2) Measures of non-verbal behaviour. For example, Paul Ekman and Maureen O’Sullivan, ‘From flawed self-assessment to blatant whoopers: The utility of voluntary and involuntary behaviour in detecting deception’ (2006) 24 Behavioral Sciences and the Law 673, and

(3) Measures of words and descriptions used. For example, Matthew Newman, James Pennebaker, Diane Berry, and Jane Richards, ‘Lying words: Predicting deception from linguistic styles’ (2003) 29(5) Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 665; Bruno Vershuere, Glynis Bogaard and Ewout Meijer, ‘Discriminating deceptive from truthful statements using the verifiability approach’ (2020) Applied Cognitive Psychology.

However, these cues are unlikely to be sufficiently reliable for use in legal procedures, in part because they are subtle and not always present.

Techniques to Make Deception Clearer

In order to help people better distinguish truth and lies, researchers have developed techniques to increase relevant differences between those telling the truth and those lying. For example:

Children and Trauma

Special care should be taken when examining the testimony of people who have been subjected to trauma, particularly children. This special care is required because cues typically associated with lies may be predictably present even where the person giving testimony is telling the truth. For example, victims of trauma, particularly when young, might be susceptible to what is known as memory “blending” which can lead to inconsistencies in accounts.

False memory

Memory is not always accurate, and false memories can arise either spontaneously or as the result of suggestion.

Charles Brainerd and Valerie Reyna, The Science of False Memory (Oxford University Press, 2005).

Elizabeth Loftus, ‘Make believe memories’ (2003) 58(11) American Psychologist 867.

Mark Howe, Lauren Knott and Martin Conway, Memory and Miscarriages of Justice (Routledge, 2017).

Spontaneous false memory

Spontaneous false memories are false memories that arise without external influence as a result of internal processes. For example, a false memory may arise where a person encodes the “gist” of an event, and later recalls this gist but imposes incorrect specific details on it as a result of forgetting true specific details. For example, research has shown that people who see a list of words relating to sleep are likely to later remember that they heard the word sleep even when they did not.

Research shows that spontaneous false memory:

(1) Is more likely in adults than children.

(2) Can arise as the result of source confusion (inappropriately connecting experiences). This confusion can lead to identifying a familiar but innocent person as the culprit of an offence, or to believing that an imagined event really happened.

(3) May be more likely in certain people or situations, for example as a result of individual differences, differences in experiences, or emotion.

The influence of suggestion

False memories can arise as the result of external suggestion, for example as a result of leading questions in interviews that suggest a particular answer to the person being interviewed.

Research shows that false memory arising from suggestion:

(1) Is generally, but not always, more likely in children than adults.

(2) Can arise as a result of receiving misinformation or as a result of suggestive questioning (i.e. being asked leading questions).

(3) May be more likely in some people than others

Interview protocols

Interview protocols, including the ‘Cognitive Interview,’ have been designed to increase true recollection while minimising errors and false memories. Where such protocols are not followed, the risk of memory corruption and errors is higher.

Distinguishing true and false memory

Research has not yet identified a reliable way to distinguish true and false memory, although factors discussed above can help provide insight into whether a memory is likely to be true or false. For example, a memory is more likely to be false where a person has experienced suggestive questioning.

Researchers have attempted to find ways to distinguish true and false memory by analysing the memory itself. The criterion which has been found to best differentiate true from false statements is the level of detail reported. True memory reports tend to contain more detail, particularly sensory detail such as sight, sound, feel, taste, or smell, than false memories do.

However, research has also shown that some false memories (known as rich false memories) contain significant amounts of detail.

Importantly, research suggests that non-experts may rely on cues that have been shown not to be accurate when assessing whether a memory is likely to be true or false. For this reason, there is a risk that non-experts including jurors could make predictable mistakes when assessing testimony.

For example, non-experts tend to have high levels of believe that ‘repressed memories’ are accurate when compared to experts, who are much more skeptical.

Similarly, non-experts tend to associate witness confidence with greater witness accuracy. Scientific research shows that while confidence generally predicts accuracy, this relationship can be seriously compromised under certain conditions.

Potential mistakes based on mistaken beliefs have the potential to lead to both wrongful convictions and systematic failures to successfully prosecute in cases where prosecution may be appropriate.