Evaluating lay testimony is important in both civil and criminal justice. For example, whether a witness is reliable can make the difference between conviction and acquittal of a defendant, or a person being granted leave to remain rather than facing deportation. However, It is difficult to determine accurately whether a person providing testimony is being truthful and is likely to be accurate in their assessments.

We are working on a large-scale evaluation of testimony evaluation, that examines the basic science of testimony evaluation and translates scientific research into practical and normatively appropriate legal procedure and best-practice guidelines.

We launched our report on testimony evaluation at the CCRC on 09/02/2026. You can find a copy of the report below. We would love to hear any feedback or questions in relation to the report.

Judgments About Memory

The legal system relies on jurors being able to accurately assess the memory of others by virtue of having had their own experiences with memory. However, our work suggests that in some ways people perform extremely poorly when making judgments about the memory of others, and that their own experiences with memory can actually be misleading.

Our work in this area has looked at a type of “social metamemory,” specifically the ability of people to predict what others will remember from a given stimulus.

This work showed that people performed no better than chance when predicting what others would remember if they experienced a stimulus. It also showed that peoples own experience of a stimulus can bias their judgments of whether other people would remember it, even when those other people have experienced it differently. If a juror views a large image of a potential perpetrator, for example, they believe that it is more likely a witness to a crime would remember that person than when a juror views a small image of a potential perpetrator, even though the size of the image the juror sees is not relevant to how the witness experienced the event.

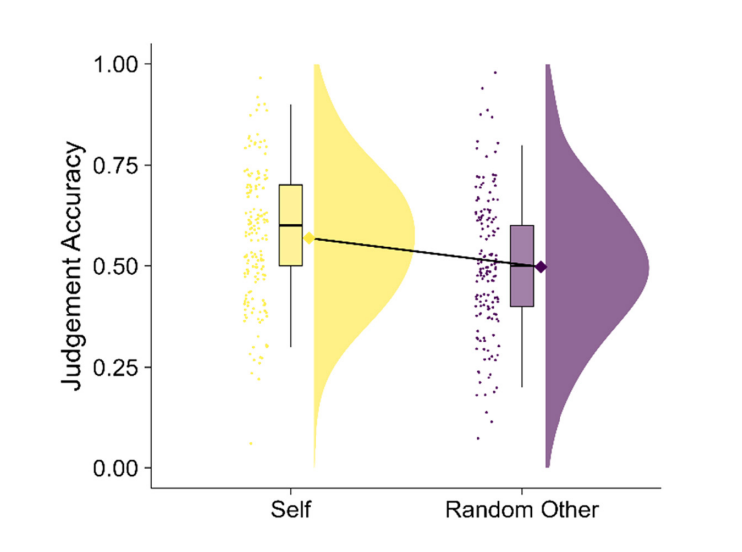

Predicting own Memory vs others memory

The graph below is taken from the publication discussed above, and shows people’s accuracy when making predictions about own memory vs. when making predictions about the memory of others. As the graph shows, people were better than chance at making predictions about their own memory but not when making predictions about the memory of others.

Why does it matter?

Predictions about how likely it is that others would remember a stimulus if they experienced it are important since an important question when assessing witness testimony at trial is what you would expect a witness to remember had they experienced an event as alleged:

- No memory for an offender that jurors would expect a witness to remember might be taken as strong evidence that a person a juror can’t recognise is not the offender.

- No memory for aspects of a crime scene that jurors would expect a witness to remember if events occurred as they alleged might be taken as strong evidence that a witness is not credible.

Our work suggests that jurors own experience does not clearly facilitate accurate judgments about the memory of others. Everyone’s memory works differently, and one persons experience of memory may not be informative in making judgments about the memory of another person. This reality has important implications for the role of the jury when assessing memory, and suggests more guidance than is currently given may be necessary.

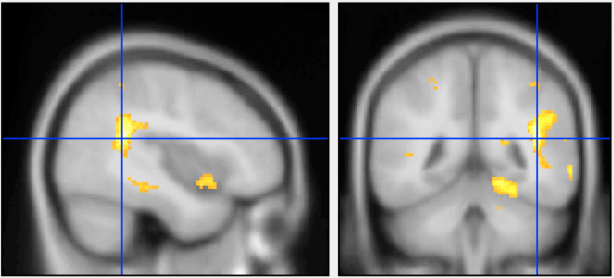

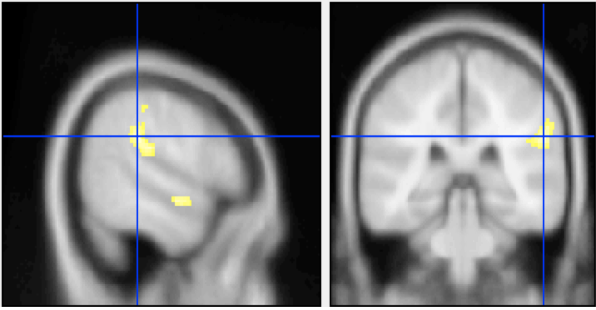

Neural Mechanisms Underlying Assessments of identification evidence

Existing work has provided important insight into how people evaluate identifications made by others. This work has shown biases in assessments (e.g., Jones et al., 2023) and also a failure to draw on and apply relevant knowledge or information (e.g., Helm, 2021). Based on this work, researchers have speculated that juror evaluation of witness testimony (and evidence more generally) is largely intuitive, involving social cognition. While behavioural work has provided important insight in this area, it is limited in the extent to which it can distinguish cognitive mechanisms underlying evaluations and related biases. In one of our current projects, we are examining neural activation to provide new insight here.

For example, we are examining whether biases in the interpretation of identification evidence are associated with reduced neural activation in structures associated with deeper information processing (e.g. the LPFC or OFC) and whether patterns of activation in evaluations resemble activations that have been demonstrated in motivational processes, social processes, reward-based processes, or in generic prejudice.

Key stats

Judgments About Credibility

Our research draws on existing work in cognitive science about the inferences that are important to people when making judgments about the credibility of others. We have drawn together existing research to examine what is likely to influence jurors in making judgments about who to believe in cases involving serious sexual offences (where complainant and defendant testimony is the only primary evidence) and have also conducted original experimental work to examine how these influences are likely to be operating in modern juries.

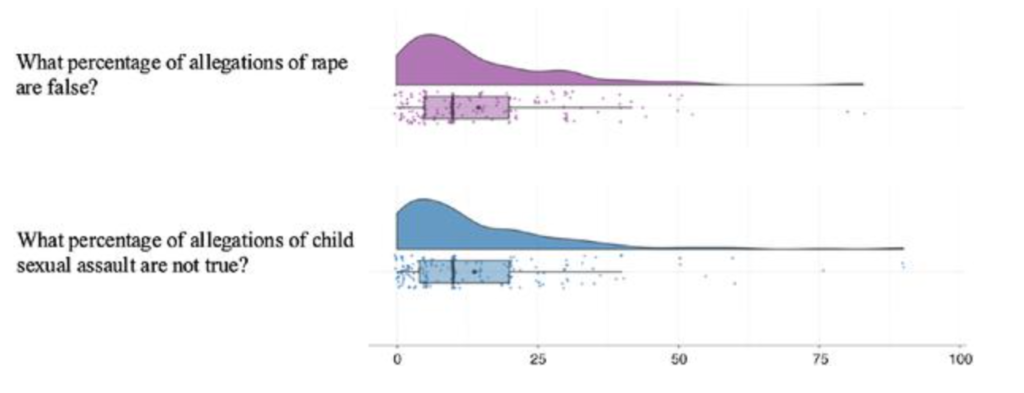

Systematic over-estimation of false allegations

Evidence-based research suggests that roughly 5% of allegations of sexual assault are false. Our work shows that it is likely that many jurors are systematically over-estimating the prevalence of false allegations, and that this over-estimation is likely to be influencing credibility judgments in practice – specifically leading people to downgrade their ratings of how credible a complainant is.

This work has also shown how differences in perceptions of how common false allegations (and underlying offences) are can partly explain why male and female jurors, and jurors with different cultural worldviews, tend to reach different verdicts in these cases. The systematic differences in decision-making, particularly among male and female jurors, suggests consideration should be given to gender balance on juries in these cases.

Importantly, our work has also explored how providing information to jurors might influence their perceptions of the prevalence of false allegations and, relatedly, their verdict decisions.

Biases and Misconceptions

Importantly, our work shows how biases and misconceptions may feed into the jury decision-making process in cases involving serious sexual offences, even where jurors do not explicitly endorse “rape myths.” This reality is important because existing interventions to improve the quality of decisions in this area still largely focus on dispelling rape myths, rather than broader, potentially problematic, influences on decision-making.

Our work seeks to develop and test interventions with the potential to improve the quality of juror decisions in this area in order to benefit both complainants and defendants.

Key Papers

Memory and Credibility Evaluation in PRactice

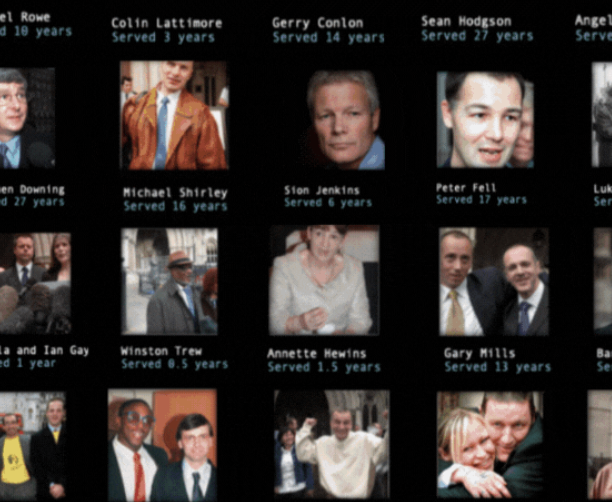

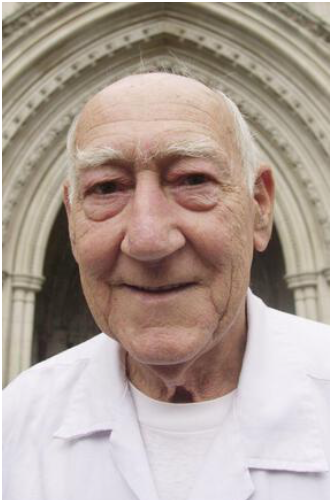

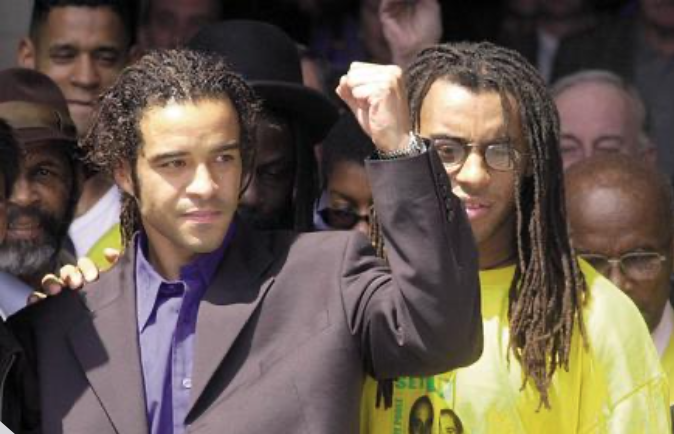

Our current miscarriages of justice registry contains details of 466 miscarriages of justice that have occurred in the UK since 1970. Of these, 25.32% involved misleading eyewitness evidence from a non-complainant and 11.59 involved misleading witness testimony from a complainant. Through examining these cases we can better understand miscarriages of justice in this area and how they might be addressed.

The cases clearly demonstrate difficulties that jurors face when deciding whether an account given by a witness is accurate. In many cases, jurors seem to have been convinced by witnesses who later evidence demonstrates were very likely to be lying or mistaken. There is more detail on these cases in our witness evidence wiki.

Key Paper

The cases

Evidence Based Instructions

The instructions currently given to jurors in cases in which eyewitness memory is central evidence rely on providing jurors with information and presuming that the information will (1) effectively lead jurors to change their beliefs, and (2) allow jurors to effectively apply the information in the case they are deciding. However, psychological theory suggests that merely providing jurors with information may not do either of these things effectively.

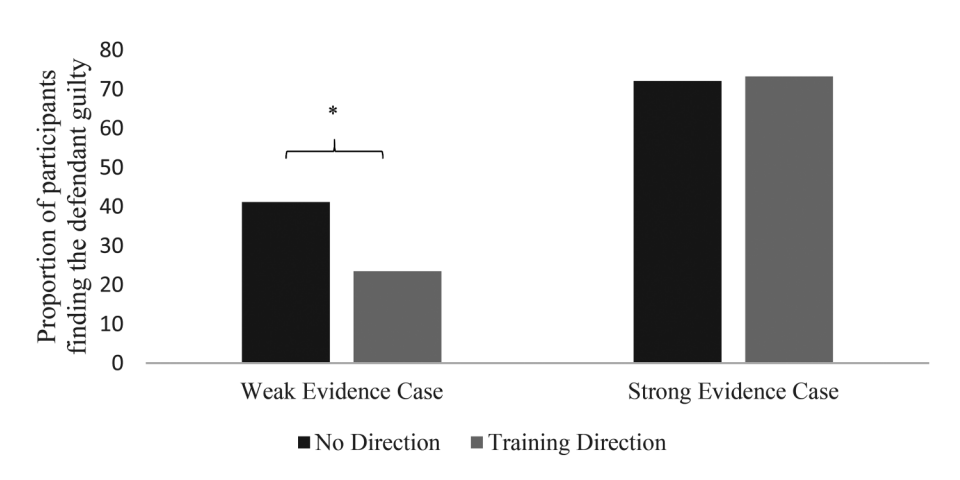

Our work has drawn on psychological theory to design and test evidence-based instructions (which we have referred to as “training directions”) with the potential to more effectively lead to belief change in jurors, and to allow jurors to apply information in practice. In an experimental study comparing the instructions we have devised to more standard instructions in a case context, our training instructions (but not the more standard instructions) brought juror beliefs more in line with scientific evidence, and also fed through appropriately into mock legal judgments.

Key Paper

For more information on our work on testimony evaluation, please read our Research Briefing document or get in touch via the contact us page.