Becky Harwood

Proven Innocent After 11 Years On Death Row: Lessons From The Case of Ron Williamson

Proven Innocent After 11 Years on Death Row: Lessons From The Case of Ron Williamson.

‘In this blog post, our research assistant Carolene discusses the case of Ron Williamson, and what it can teach us about the justice systems in the United States and here in England and Wales‘

John Grisham, a best-selling author and recipient of various accolades, writes fictional books on the most horrific of crimes. From his own imagination, using his legal background as a barrister, he has written numerous legal fiction stories which have caught the attention of many around the world for their horrific nature. For a non-fiction story to have caught his eye, it must have been shocking. To this day, he has only ventured into writing one non-fictional book in his career; when questioned he said that this was such a fundamental miscarriage of justice that he felt the need to share it.

This is the story of Ron Williamson.

Ron Williamson was a successful baseball player- a big name in his small town of Ada. Ada Oklahoma, mid America, is described by Grisham as old fashioned and rural, the sort of American small town you see in the movies. Except this small town had a loud character, and that was Ron Williamson. Disturbing the seemingly peaceful small town, following his failed baseball career due to a shoulder injury, Ron had to move back home to his parents’ house. Suffering from depression he turned to alcohol to cope, and his mental health soon deteriorated. As a result, he became known as a so-called town weirdo, and people called the police on him because he would drunkenly sing along the streets at night or randomly decide to mow people’s lawns without their permission. To many, these are classic signs of someone not coping well mentally. But to the Ada police department these were signs that he may be a horrific murderer and rapist. The link seems so tenuous, because it is. On December 8th, 1982, Debby Carter was murdered and raped when she returned from work after working at a bar. The details of her brutal rape and murder are horrifying, described by the police as the worst they had ever seen. After 5 years of no successful arrests in the murder investigation, the police turned to Ron Williamson.

The best evidence the prosecution could present was a dream that Ron described to the police.

In 1988, along with his drinking buddy Dennis Fritz, Ron Williamson was arrested for the murder. The evidence used to convict him can’t even be called flimsy; it was worse than that. The best evidence the prosecution could present was a dream that Ron described to the police. After being interrogated for days on end and hearing the story all over town, Ron described to the police a dream that he had where he had murdered and strangled Debby. This dream was treated as a confession. To the Ada police the dream seemed sufficient to suggest that Mr Williamson was guilty. In fact, Ada has become infamous for this. In a book by Robert Mayer titled The dreams of Ada, Mayer describes how the small town was so obsessed with securing convictions that several of their convictions were based on “dreams” reported by the defendants. In Grisham’s book he reveals the story of Tommy Ward and Karl Fontenot who were convicted for the murder of a store clerk based on a dream scenario that they described. These men spent 35 years in prison before being released after the State conceded that they were wrongly convicted.

In addition to this poor evidence, there was clear corruption at the heart of Ada’s judicial system. Evidence suggests that the lead prosecutor, Bill Peterson, forced other prisoners to lie and create stories about Mr Williamson. He forced a witness to say that Mr Williamson was at the bar where Debby worked the night of the murder and made a deal with another prisoner, Glen Gore (remember this name for later), to say that Mr Williamson had confessed to the murder whilst waiting for trial, despite Mr Gore being in another part of the prison.

So, the prosecution’s evidence was a dream confession and false witness testimony. Despite this, Ron Williamson was still found guilty at his trial. Since this was Oklahoma, a state which allows the death penalty, Mr Williamson was sentenced to death. However, the death penalty was not the only torture facing him; his increasingly deteriorating mental state was equally as tortuous. Mr Williamson was already suffering from mental health conditions, however being locked up exponentially worsened his mental health problems. Tragically, the state refused to address Mr Williamson’s mental health problems even though he was clearly suffering. He would have episodes of yelling from his cell to then staying in bed for days. One of the prison doctors even recognised the severity of his deterioration and for years requested help, only to be rejected. Where Mr Williamson did receive help, it was minimal and not a sustainable solution. In the US there have been proposed bills to ban the death penalty for mentally ill prisoners, as they are not aware of the situation and consequences (see here). This, however, has been consistently rejected. The State did not seem to care about Mr Williamson or the truth, they focused exclusively on justice for Debby and in doing so tortured an innocent man. Mr Williamson spent 11 years on death row, and at one point was only 5 days off being killed.

Thankfully, the Innocence Project agreed to take on this appeal and with little investigation needed, the lawyers soon realised the absurdity of this case. How could someone be sentenced to death in the absence of any reliable evidence? His lawyer Mark Barrett highlighted the clear issues in the prosecution’s case and Judge Seay ordered a retrial in 1999.

In the late 90s, scientific advances meant that it was possible to accurately identify someone’s DNA when biological material was left at the crime scene. For Ron Williamson, it was crucial in excluding him as the true perpetrator of the crime. The semen found inside Debby Carter did not belong to him and that his DNA was not found at the crime scene. Ron Williamson was finally exonerated on April 15, 1999, after spending 11 years on death row.

Ron was the 78th inmate released from death row since 1973, proving that there are innocent people sent to prison and likely even to their death

This is beyond doubt a massive miscarriage of justice. Ron was the 78th inmate released from death row since 1973, proving that there are innocent people sent to prison and likely even to their death. This is unthinkable, however when we look at this case it is easy to see how failures in investigation led to the wrongful conviction. If those investigating the crime hadn’t been so determined to prove Mr Williamson was guilty then the true offender could have been found. Especially since the true offender was in front of them the whole time.

After further DNA tests, it was revealed that the semen inside Debby Carter belonged to Glen Gore. The prisoner who the prosecution colluded with to be a witness against Mr Williamson.

Mr Williamson’s case is clearly a devastating miscarriage of justice. It can also teach us an important lesson about juror decisions in criminal cases: under the right conditions jurors may find defendants guilty “beyond reasonable doubt” even on the basis of relatively tenuous evidence. This reality may be particularly true in cases like Mr Williamson’s, where all involved are likely to be desperate to obtain justice for the victim. So, what are the implications of this for the justice system?

1. The death penalty should never be an available sentence.

The fact that defendants risk being convicted on relatively little evidence means that while the death penalty is legal there will always be a risk that defendants who are innocent will be executed. This conclusion is supported by empirical research into the death penalty.

In the US 136 prisoners have been released from death row since 1976, some of whom it is now clear are innocent. One recent academic study used statistical analyses and available data to suggest that at least 4.1% of death sentences in the US are likely to be being imposed on innocent people (see here). This highlights a serious risk that the death penalty is being used on innocent people. If the death penalty was the sentence given to Mr Williamson, it can clearly be handed down in cases where the evidence against a defendant is far from overwhelming. And not all defendants will have the ability to later demonstrate their innocence through DNA testing.

Whilst we cannot be sure whether those who have already been executed are innocent, there are several cases which would indicate that this is certainly the case. For example, Ruben Cantu was executed in 1993 after being convicted of murder during an attempted robbery. Tragically, after his execution the key witnesses in the case came forward saying they felt pressured and afraid of the authorities and did not accurately tell the truth. Additionally, Cantu’s co-defendant signed a sworn confession that Cantu was not with him on the night of the crime, thus resulting in the district prosecution himself admitting the death penalty should not have been sought. Luckily for Ron Williamson, he was saved from the death penalty – though only by five days. From this case alone, it is clear that we must question just how many innocent people have been wrongly executed. The Netflix series Innocent man, which is based on Mr Williamson’s story as well as the series The Innocence Files highlight the failures within the judicial system. Given these failures it is hard to see how anyone could advocate for the death penalty even with safeguards. Safeguards clearly do not always work.

2. Further regulation of witness testimony from certain categories of defendant may be necessary.

Mr Williamson’s case shows how several pieces of unreliable evidence may be very convincing to a jury, and may even convince them that a defendant is guilty beyond reasonable doubt. It also adds to research showing that jurors are likely to have difficulty detecting deception in witness testimony.

Evidence from jailhouse informants or others ‘co-operating’ with the police is important in many cases beyond Mr Williamson’s. In a May 2015 ‘Snitch Watch’, the National Registry for Exonerations in the USA found that eight percent of all exonerees in their Registry (119 of the 1,567 cases) were convicted in part by testimony from jailhouse informants. They found that this kind of testimony was more likely to have contributed to miscarriages of justice in more serious cases.

Evidence from witnesses who may be incentivised to lie is not just problematic in the USA. Our database of miscarriages of justice in the UK contains details of 34 miscarriages of justice involving evidence from police informant’s or co-defendants (see here). For example, Gary Ford was convicted of robbery and burglary in 1996 based largely on the evidence of a man called Karl Chapman, who was later shown to have received inducements to give evidence against him. Adam Joof, Levi Walker, Antonio Christie, Michael Osbourne, and Owen Crooks were all convicted of murder largely on the basis of the testimony of a co-defendant who claimed to have witnessed the shooting. Their convictions were overturned on appeal when undisclosed evidence showed that known dishonesty of the co-defendant had not been disclosed to the defence. David Tucker was convicted of robbery based largely on evidence from his co-accused, but was acquitted when evidence showed the co-accused had a clear motive to implicate Mr Tucker regardless of guilt.

This evidence suggests certain types of witness, including jailhouse informants and co-defendants, who are particularly likely to be incentivised to lie. This risk of incentivisation, combined with the difficulties jurors are likely to have in detecting deception, mean that enhanced procedures to protect defendants in these types of case may be necessary. These protections may include enhanced disclosure requirements, or even, in certain cases, excluding evidence from the jury all together based on the risk of an unknown incentive to lie being present. Exclusion of evidence may be particularly appropriate in cases involving jailhouse informants.

Sadly, Ron Williamson died in 2004, at the age of 51, just five years after being exonerated. Thankfully, he was a free man when he died. The lessons learned from his case can be used to help prevent similar injustices being inflicted on other defendants.

For further information on this case, John Grisham’s The Innocent Man book is available online, and a Netflix series named The Innocent Man also tells Mr Williamson’s story.

Author Carolene Clarke EBJL Miscarriages of Justice Student Research Assistant.

#FalseGuiltyPleas #InnocentDeathRow #EBJL #EvidenceBasedJustice #MiscarriagesOfJustice #FalseConfession #CriminalJustice #RonWilliamson #JonGrisham

How can psychology maximise the accuracy of forensic science?

How can psychology maximise the accuracy of forensic science?

Emerging research over the last decade has shed light on the risk of error in forensic science. Research from the Evidence-Based Justice Lab at the University of Exeter aims to help tackle this issue by drawing on cognitive psychological research to develop training programmes and selection tools to maximise accuracy and reduce errors in forensic science.

One of these errors can be seen in the case of Shirley McKie: a Scottish police detective accused of leaving her fingerprint at the scene of a murder. Despite denying ever having entered the crime scene, Ms McKie was arrested and charged with perjury. But it was later revealed that the fingerprint examiners originally involved with the case had made a substantial error: the fingerprint at the crime scene never belonged to Ms McKie – who avoided up to eight years in jail on the charges and was later awarded £750,000 in compensation.

So how can these kinds of errors be avoided in the future?

We know that forensic examiners do make errors. Accuracy levels differ between individual decision-makers and between different forensic disciplines – accuracy can range from approximately 90% in some disciplines to only 65% in others. However, these kinds of errors can be reduced by using scientific methods to improve overall professional accuracy. This is generally attempted via training but unfortunately, there is not a lot of published data that shows whether or not this helps. Some research even shows the opposite and suggests that some forensic training programmes don’t generally improve short-term accuracy.

In order to develop effective training programmes to improve accuracy, we need to understand what goes on inside practitioners’ heads when they make accurate decisions. What is it that makes them experts compared to the average person? There are different perceptual and cognitive processes that examiners use when they perform their work – but we don’t yet know much about these. And understanding how examiners make accurate decisions will be crucial to developing programs that could train other practitioners to use these same processes to increase their own accuracy.

So what kind of processes do practitioners use in their work?

My research has shown that examiners use a whole host of different psychological processes. One of these is called featural processing and a practitioners’ ability to break images down into small parts and compare these parts separate to the ‘holistic’ image. For example, a facial examiner who looks at passport images to detect fraud might break down two faces images into separate parts (e.g. eyes, nose, ears, mouth) and then compare these separately between the two images. Breaking the image down into separate pieces can help an examiner take their time and properly look at which parts of the face might look similar or dissimilar in order to help them decide if they are of the same or different people.

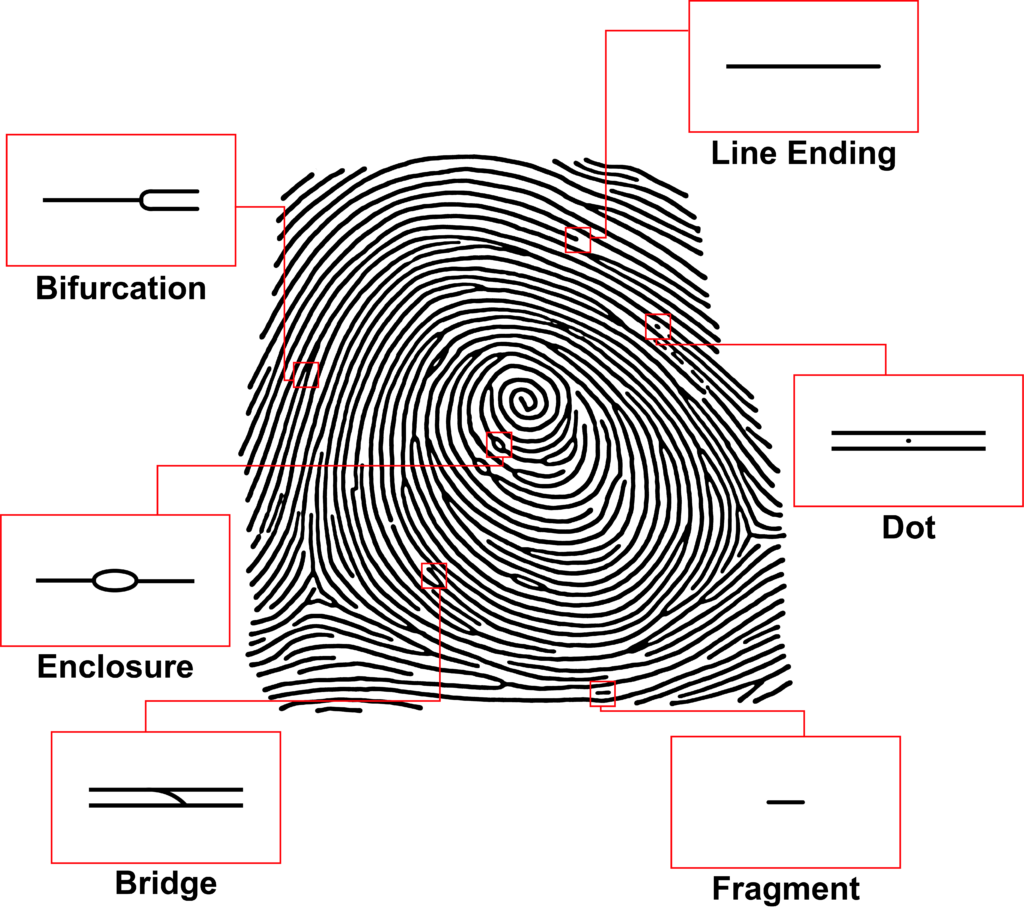

Another process is called statistical learning and is a practitioners’ ability to learn how often features occur in forensic evidence and then use this information to help decide how likely it is two samples are from the same person or different people. For example, fingerprint examiners might learn over some time that certain fingerprint features (e.g. ‘bridges’) are rarer than other fingerprint features (e.g. ‘bifurcations.’). As rarer features are shared between fewer people in the general population, if a fingerprint examiner saw two similar-looking ‘bridges’ in two fingerprints, those two fingerprints would be more likely to be from the same person than if they shared a more common feature.

So where do we go from here?

These are just some of the cognitive and perceptual processes that help examiners in their work. But we must understand more about them in order to develop scientifically-based training programs to improve expert performance. When we understand how practitioners make accurate decisions, we can then use this information to train other practitioners to increase their own accuracy. These training programmes would be even more important for new forensic trainees to help fast-track their expertise. Eventually, this sort of research could even be used to design selection tools to recruit new forensic practitioners on the basis of high-performers on skills we know are important in forensic science.

If you’re interested in learning more about this, please feel free to take part in our latest study run by the University of Exeter and Arizona State University investigating how training could improve performance in fingerprint-matching tasks. We are recruiting fingerprint examiners and anyone else that might want to be in with a chance to win a USD$500 VISA gift-card!

Can I go back to school now? False confessions and false guilty pleas in children.

‘Can I go back to school now?’ False confessions and false guilty pleas in children.

‘Although reforms may go some way to protect children from falsely confessing, children are still at risk in our criminal justice system which requires them to make decisions capable of impacting the rest of their lives, and subtly pressurises them to make those decisions a certain way.’

In 2019, we watched the re-telling of the infamous Central Park Five wrongful conviction case on Netflix, ‘When They See Us.’ Five school kids were coerced into falsely confessing to a violent rape and assault. Twelve years later they were exonerated when someone else confessed to the crime. But why did they confess if they hadn’t committed the crime? Has this happened in the UK? And are young people still falsely confessing today?

Research shows that false confessions are not as rare as you might think, especially in children.

Children are particularly vulnerable to pressure, coercion, and suggestion, and also lack maturity in judgment. This means that children may falsely confess even under conditions that would not seem coercive to adults. In one well-known false confession case in the UK, Colin Lattimore, Ronnie Leighton and Ahmet Salih, all under 18, falsely confessed to murder after hours of interrogation and without legal advice. They each spent three years in prison as a result of these false confessions until new evidence showed they could not have committed the murder as the prosecution alleged.

Scrutiny of the treatment of the three boys and other notable cases from the mid-1970s, such as the Birmingham Six and Guildford Four cases, helped bring about sweeping legislative changes and the introduction of the 1984 Police and Criminal Evidence Act, commonly known as PACE. The question is, does 1984 PACE provide enough safeguards to account for vulnerabilities? Or is reform needed to protect children?

How effective has PACE been?

A common theme in false confessions in children is the absence of legal representation or legal advice.

The immediate thought to anyone sitting at home watching Netflix would be to question why did the Central Park 5 not ask for legal representation or advice? But like anyone not guilty of a crime, why bother engaging with legal advice if you know for certain you are innocent. A reasonable assumption made by anyone, let alone a child, unaware of the legal repercussions they may soon face. PACE 1984 introduces safeguards to protect all defendants from pressure to falsely confess. For example, detained suspects now all have the right to free legal advice and the right to be represented by a solicitor. There is far less evidence of false confessions in children (and in defendants overall) since the introduction of PACE. However, there is also evidence that the problem has not gone away and that the provision of legal advice is not a panacea for false confession. For example, Oliver Campbell, who was a highly vulnerable 19-year-old when convicted of murder in 1990, said he confessed to the murder because he was “put under pressure” to say things he didn’t want to say, and “felt scared.” He has been identified as highly suggestible, and claims that he had nothing to do with the murder he confessed to.

In addition, it should be noted that the effectiveness of legal representation can vary. Recent work has raised questions about the quality of legal representation in children, particularly in the youth court, and work is being done by both the Solicitors Regulatory Authority and the Bar Standards Board, to improve the quality of legal representation for children.

The reforms brought about by PACE are also unlikely to protect children from feeling pressure to confess in a different way – through pressure placed on them by the legal system to admit guilt. Specifically, children often face compelling pressures and incentives to either admit guilt in exchange for a caution (and avoid prosecution altogether) or to plead guilty in court.

Incentivised false confessions – guilty pleas and cautions.

Children accused of criminal offences often have the opportunity to avoid prosecution, but only if they “admit” involvement in an offence. An admission is required to accept a caution, and is often required by diversion from prosecution schemes. As a result, children face pressure to admit guilt to avoid having proceedings brought against them. These admissions, while not as damaging as a guilty verdict in court, can have important consequences for their futures.

Where they are proceeded against in court, children can sometimes avoid a custodial sentence by pleading guilty where they would risk a custodial sentence if they proceeded to a full trial. These discounts are often thought of as rewarding those willing to admit guilt and take responsibility, but they can be equally viewed as creating a trial penalty, where defendants know that they may effectively be punished for exercising their right to a trial.

These incentives to admit guilt create a system in which young people have to consider a variety of factors other than factual guilt when deciding whether to make an “admission.” Young people might admit guilt to avoid court, to avoid custody, or to avoid a longer sentence, even when innocent. The developmental vulnerabilities discussed above make them particularly vulnerable to doing so.

Dr. Helm’s experimental work supports this idea by suggesting that young suspects are particularly susceptible to pleading guilty when innocent due to their cognitive developmental immaturity. These conclusions are also supported by field work in the US context (see here, for example).

This new form of coercion to admit guilt is more subtle than the pressures outlawed by PACE, but may be equally important, if not more important, in creating miscarriages of justice in children. This is particularly important since vulnerability resulting from relatively low intelligence and cognitive ability may disproportionately disadvantage youth who are at an increased risk of offending due to their socioeconomic status, family structure and wealth. The nexus between violence and poverty can enhance the vulnerability of young suspects and further negatively influence the decision-making process for a young suspect. In a recent paper in the Journal of Law and Society, Dr Helm examines these issues and concludes that children need additional protection in our criminal justice system which is heavily reliant on incentivised admissions.

Conclusion:

So the show is over, and no, Netflix, we do not want to continue watching. The question remains, however, are young suspects, especially suspects who have limited intelligence compared to their peers, adequately protected by the UK legal system?

Young suspects are handicapped by their developmental immaturity, yet the legal system still requires them to make decisions capable of impacting the rest of their lives, and subtly pressurises them to make those decisions a certain way.

While pressure pushes children to make these decisions a certain way, through coercion or incentivisation, children will admit guilt when innocent. More research is currently underway to help and reduce the extent to which innocent children falsely admit guilt. Hopefully, this research can inform policy to ensure that innocent children can comfortably go back to school unharmed and with their future plans intact.

Author Haneet Parhar EBJL Miscarriages of Justice Student Research Assistant.

Follow us on Twitter @ExeterLawSchool @RebeccaKHelm and LinkedIn https://www.linkedin.com/company/evidence-based-justice-lab

For a list of Dr Helm’s academic publications on guilty pleas, see the publications page of our website: https://evidencebasedjustice.exeter.ac.uk/publications/

For more information on our data and research on guilty pleas, see the guilty plea decisions page of our website: https://evidencebasedjustice.exeter.ac.uk/current-research-data/admissions-of-guilt/

For more information on guilty pleas in actual cases in England and Wales, search for guilty plea cases in our miscarriages of justice registry:

https://evidencebasedjustice.exeter.ac.uk/miscarriages-of-justice-registry/the-cases/overview-graph/

#FalseGuiltyPleas #InnocentChildren #EBJL #EvidenceBasedJustice #MiscarriagesOfJustice #FalseConfession #CriminalJustice #CentralParkFive #ColinLattimore #RonnieLeighton #AhmetSalih #PACE1984 #PACE

Why Confess To A Crime You Didn’t Commit?

‘The confession tapes’ shed light on the reasoning behind false confessions

The Netflix documentary series ‘The Confession Tapes’ exhibits the experiences of defendants in multiple US cases in which they have been convicted of crimes they claim they did not commit, but confessed to during police interrogations. This issue is more common in the UK than it may seem at first, with 26.8% of Miscarriages of Justice cases reported in the EBJL UK Miscarriages of Justice Registry classified as having involved a false confession.

The Confession Tapes not only highlights false confessions as a compelling issue within the justice system, but also helps the viewer to understand the circumstances behind why anyone would confess to a crime they did not commit. It is clear from The Confession Tapes that while so many automatically think that ‘I would never confess to something I didn’t do’, it really could happen to anyone, and justice may never be served for those convicted due to confessions they felt they had no choice but to make.

The EBJL Registry contains a false confession ‘wiki’ devoted to discussing the situations in which innocent defendants may confess to crimes they have not committed, and the research that can help inform assessments of whether a confession may be false. Together, the wiki, and The Confession Tapes, highlight three main reasons innocent people confess – custodial and interrogative pressure, psychological vulnerability and lack of transparency surrounding evidence.

Three main reasons why innocent people confess – custodial and interrogative pressure, psychological vulnerability and lack of transparency surrounding evidence.

Custodial and Interrogative Pressure

There are many safeguards in place within both the US and UK to prevent the police from abusing their power in an interview scenario. PACE 1984 governs the UK’s safeguards, giving the accused the right to legal advice and to have a lawyer present in the police interview, providing the right for an appropriate adult to be present should the accused be mentally vulnerable or a juvenile, prohibiting oppressive interviewing, regulating of the length of detention and interview, and ensuring tape recording of police interviews. The US has similar rights derived from the US Constitution, yet both The Confession Tapes suggest police may apply pressure to a defendant with the intention of inducing a confession more regularly than people think. Where this occurs, it is important to consider whether the specific conduct is unlawful or simply against the spirit of the law, particularly in the context of emotional manipulation.

In The Confession Tapes episode titled ‘The Labor Day Murders’, Buddy Woodall is interrogated by police in relation to a double homicide. At first he firmly stated that he was not there nor was he involved in the homicides. There was very little forensic evidence against him, a few hearsay statements from people he knew and some circumstantial evidence concerning his whereabouts when a phone call was made to lure the victims to the scene of the murder, none of which would be likely to convict him. Whilst interrogating Woodall with no lawyer, the police turn on the video camera 10 hours into the interview, where we see them interviewing in an extremely coercive manner, practically hypnotising him, coming up with different scenarios to confuse his memory and emotionally manipulating him into confessing to witnessing the murder. The police tell him multiple times to ‘say it and be done with it’, providing him with only one way out of the tense and distressing environment they have created, and falsely allowing him to believe he will not be punished for what he’d allegedly done if he admitted it (a tactic known as ‘minimisation’). The footage of the interview is disturbing, as it is blatantly clear how the power dynamic of the three policemen compared to one distressed, exhausted suspect is exploited to fit the narrative the police want to create. Although Woodall pleaded not guilty and still maintains that he was coerced into confessing, he remains imprisoned in Georgia for a crime he claims he did not commit, largely due to the confession he made after 10 hours of intensive, suggestive, leading questioning without a lawyer.

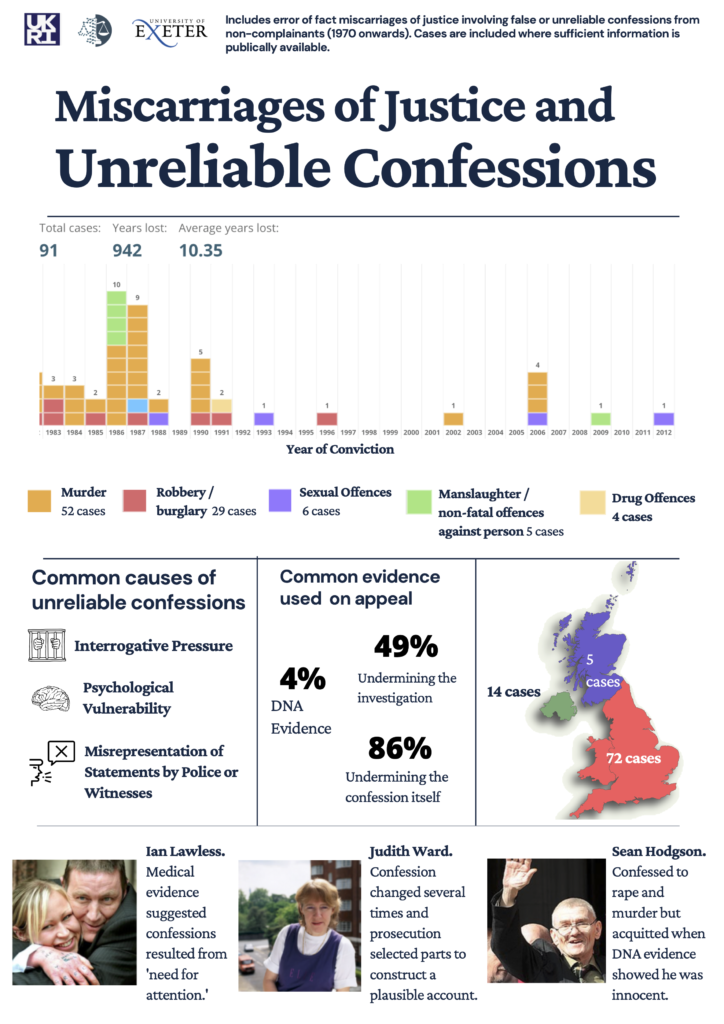

This is not an isolated incident to occur, and the EBJL database suggests that similar incidents have occurred in the UK, where a total of 942 years have been lost in the UK justice system due to false confessions, some of them in an eerily similar fashion to Woodall’s case. A well-known example of coerced confessions is The Guildford Four, convicted of murder for blowing up two pubs in Guildford. All four of the accused signed confessions under severe police coercion, perhaps in a more violent manner compared to Woodall’s experience of emotional manipulation, a horrific and unlawful experience achieving the same outcome. There may be somewhat of a stigma around a more emotionally manipulated false confession, as whether it is strictly prohibited under PACE as ‘oppression’ or is simply in bad spirit is a difficult distinction to draw, but The Confession Tapes really draws attention to the power of emotional manipulation and the desperation and damage it can cause.

A less famous UK case relating to this was Stephen McCaul, who was convicted of terrorism-related charges based on a confession made when he was 16. He, like Woodall, was interviewed for an extensive period of time (52 hours) without a lawyer or appropriate adult present, and confessed to the crimes he was accused of. There are plenty of studies suggesting sleep deprivation effects an interviewee’s suggestibility, making them more susceptible to misperceptions or demands, therefore by interviewing for extensive periods of time, police are increasing their chances of achieving a confession, true or not.

The EBJL registry suggests that miscarriages of justice arising as a result of false confessions have reduced dramatically since the early 1990s.

The EBJL registry suggests that miscarriages of justice arising as a result of false confessions have reduced dramatically since the early 1990s. This may be because custodial and interrogative pressure has reduced, or at least become more overt, since PACE. However, continuing to monitor investigative interviewing and continuing to understand how more subtle pressure may produce false confessions will be important to observe. The police v accused dynamic may mean that the problem of false confessions will not go away. The lack of justice at the end of each episode of The Confession Tapes certainly suggests that this is an ongoing problem.

Psychological Vulnerability

Psychological vulnerability can be divided into three different categories when discussing how it may provide susceptibility to false confessions; defendants under 18, defendants with low intelligence or relevant disabilities, and defendants that have a disregard for the truth or a need for attention are all categories of vulnerability. Defendants possessing any of these qualities are highly vulnerable to interrogation situations and their vulnerabilities could make it easier for a false confession to occur, creating a miscarriage of justice.

This plays a huge role in The Confession Tapes episode titled ‘8th and H’, where Clifton Yarborough, a teenager with a low IQ and learning disabilities, was convicted, along with 10 other defendants, of a violent sexual assault and murder due to his confession. In the episode, a video of the end of Yarborough’s police interview shows him recapping his confession robotically, getting many critical details wrong despite being corrected by the police multiple times, alongside an interview of his mother describing his learning difficulties. This is a powerful moment as it is obvious that Yarborough did not understand what he was signing or confessing to and how this was used to the advantage of the police. Defendants with low IQs are more likely to cater to what they think somebody wants to hear, so coupled with the fact Yarborough was a teenager at the time being interviewed with no lawyer or appropriate adult present, there was blatant room for a miscarriage of justice to take place. Yarborough’s confession played a huge role in wrongfully convicting the 10 defendants, who were sentenced to 35 years to life all due to the psychological vulnerability of the defendant that was unfairly utilized by the authorities involved.

There are multiple cases in the UK that mirror Yarborough’s experience, such as Robert Adams, who was 16 when being interviewed for a murder and was denied the support of an appropriate adult, leading to his false confession and subsequently his conviction. Similarly, a group of three men; Colin Lattimore, Ronnie Leighton and Ahmet Salih, all signed false confessions to a murder they did not commit after hours of police interrogation without a lawyer, with 2/3 of them possessing psychological vulnerabilities such as low intelligence and learning difficulties. And these cases aren’t just historic. In 2012 Jack Allen, who suffered from an identity disorder making hum suggestible and compliant, was convicted on the basis of a confession that he made in the early hours of the morning having been refused regular breaks during interviewing. During trial Mr Allen said: “I apologise for lying to the police in the interview but I had to tell them what they wanted to hear; what they told me to say.”

By putting defendants with these vulnerabilities in an interrogation situation and not allowing lawyers or appropriate adults in with them, it is clear to see how a miscarriage of justice could occur, as the lack of understanding and susceptibility to pressure exposes them to the gaps in safeguarding protection that should not exist.

Defendants with a need for attention or disregard for the truth have a slightly different psychological vulnerability in regard to confessions, as they may actively confess rather than reactively, contrastingly to those with vulnerabilities which may cause them to confess as a reaction to the pressure put on them. Cases such as Sean Hodgson and Paul Darvell involve the defendant confessing to murder due to their vulnerabilities. These cases highlight the importance of not simply accepting a confession as true, even when it appears to have been made completely voluntarily. This is important in protecting defendants but also in ensuring that true perpetrators are brought to justice. In Sean Hodgson’s case, DNA evidence recovered at the crime scene eventually showed that he was not guilty, despite initial confessions.

These psychological vulnerabilities raised in both The Confession Tapes and the EBJL certainly help to give insight as to why some people may confess to crimes they didn’t commit, as well as highlighting the necessity to afford greater protection to those who may be more at risk of doing so.

Evidence

The Confession Tapes also shares the importance of evidence as a factor for defendants when confessing to crimes they did not commit. An episode titled ‘A Public Apology’ showed Wesley Myers confessing to killing his girlfriend and setting her alight after being lied to about evidence that allegedly connected him to the scene. The police conducting the interview told him that a hair found on the scene was traced back to him, fabricated that bloody prints were found on his clothes and in his truck, and lied and told him they had an eyewitness placing him at the scene of the crime. This was all untrue, but eventually they convinced him that he had blacked out and committed the murder, leading him to declare ‘if you’ve got all that evidence then I guess I must have done it’. He signed a confession after being interrogated for 15-20 hours over 3 days, apologised in the police station to the victim’s mother, and as he was leaving the station apologised on live TV to the media which the police had called. The small amount of evidence that was not fabricated by the police was forensically unreliable so the majority of the conviction was based upon the confession that was coerced out of Myers by the lies told to him. He was eventually re-tried 16 years later and found not guilty after evidence came back conclusively determining the hair found on the scene was not his. But the damage caused by the duplicity of the police regarding evidence was already done, a significant miscarriage of justice had occured.

Another way evidence can be significant in producing a false confession is using equipment such as a polygraph test or a computer stress testing analyser as investigative tools but implying in interviews they are viewed as scientifically reliable evidence, which is not the case. Karen Boes, in The Confession Tapes episode titled ‘Trial By Fire’ is accused and convicted of killing her daughter by setting fire to her house, which she confessed to. During the 10 hour, lawyer-less interrogation, she was asked to take a polygraph test and agreed, insisting she had nothing to hide but then was told she had failed the test miserably. Although she tried to insist she didn’t know anything about the incident, the polygraph test made her doubt herself, and in a similar defeated manner to Myers, she said ‘I apparently did it according to the test’. The police had also lied and told her they found evidence of gasoline on her clothes, shoes and her fingerprints on the gasoline can, all of which were completely untrue, but contributed to her confession along with the extremely suggestive interviewing she experienced, putting her in a ‘dream-like’ state and coercing her into confessing. The confession led to her conviction, and she is currently still serving life in prison with no possibility of parole, and all appeals have been exhausted. Buddy Woodall, as previously mentioned, was also subjected to a similar test that contributed to his confession- a computer stress testing analyser was used during Woodall’s interrogation and he was similarly told he had failed the test miserably, and believed it may contribute to his conviction if he did not confess.

The Confession Tapes highlights the significance that evidence has when dealing with false confessions, and how the perception of investigative tools has a huge impact on this.

Transparency about the quality and existence of evidence is extremely vital in interrogations in order to create a fair and justiciable system for defendants to choose whether they confess, rather than being forced to when they didn’t even commit the crime. There is much less evidence of this occurring in the UK as polygraph and computer stress testing are not used as ways to aid investigations, but it is highly likely that within the 91 cases of false confession playing a role in the Miscarriages of Justice recorded in the EBJL database, the transparency of evidence has been an issue just as it has within the experiences recorded in The Confession Tapes.

It is clear there are many reasons why someone would confess to a crime they didn’t commit, whether it be due to the intense and coercive nature of interrogations, psychological vulnerabilities that cause a susceptibility to such a pressurised environment or a lack of transparency surrounding the evidence against the accused. All of these are magnified by The Confession Tapes and the EBJL Registry which shows these issues are important in the UK as well as in the US. Analysing these cases provides an answer to the question, ‘Why confess to a crime you didn’t commit?’ and suggests that we should instead be asking how we can better protect defendants given that over 940 total years of freedom have been lost in the UK justice system due to false confessions.

Author Maja Pegler – LLB Law Final Year Student at The University of Exeter & EBJL Database Research Assistant

For more information on false confessions and false memories in real cases in England and Wales see our wiki pages:

https://evidencebasedjustice.exeter.ac.uk/miscarriages-of-justice-registry/the-issues/false-confession/

https://evidencebasedjustice.exeter.ac.uk/miscarriages-of-justice-registry/the-issues/eyewitness-id/

#TheConfessionTapes #EBJL #EvidenceBasedJustice #MiscarriagesOfJustice #FalseConfession

Database of miscarriages of justice launched as part of new evidence-based justice initiative

Database of miscarriages of justice launched as part of new evidence-based justice initiative

We are really excited to be launching our new site and miscarriages of justice registry today! See below for more information.

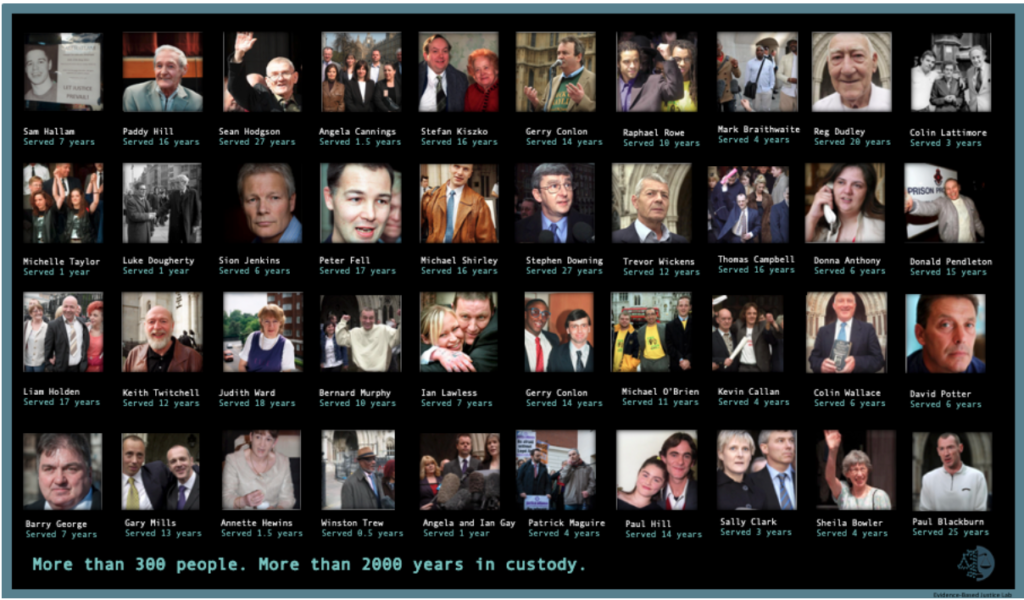

A database showing miscarriages of justice that have occurred over the past 50 years has been launched as part of a new initiative aimed at using evidence from psychology and data science to improve the legal system.

The UKRI-funded Laboratory for Evidence-Based Justice, based at the University of Exeter Law School, is a new research group working at the intersection of cognitive psychology, data science, and law. The group’s focus is on better understanding how law and policy interact with human decision-making, for example by examining how law and policy can be used to protect people from pleading guilty when innocent, to enhance evaluations of eyewitness testimony, and to limit the spread of fake news.

Dr. Rebecca Helm, the director of the lab, said: “Data and insight from science have the potential to significantly improve our understanding of how laws and the legal system operate. This understanding is important in protecting those who may be disadvantaged by weaknesses in existing law, and in ensuring the practical effectiveness of law and policy.”

The new database, created by the lab, includes the most comprehensive set of information to date about convictions overturned as a result of factual error in the UK, and covers cases in England and Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland, from 1970 to the present. It currently contains details of 346 cases, classified according to the cause of the miscarriage of justice, the offence involved and the relevant jurisdiction. According to these classifications, one hundred and forty-three (41 per cent) of the miscarriages of justice involved unreliable witness testimony, 91 (26 per cent) involved a false or unreliable confession, 75 (22 per cent) involved false or misleading forensic science, and 73 (21 per cent) involved inadequate disclosure.

The database gives a range of information about each case and includes links to relevant press and legal documentation. It also provides information about key identified causes of miscarriages of justice more generally through online “wikis” that can be added to by researchers, practitioners, and members of the public. The creators hope that the publicly available database will assist in research to improve evidence evaluation and help those who may have been wrongfully convicted themselves.

Dr Helm said: “When people discuss miscarriages of justice in the UK, they often refer to famous cases such as the cases of the Guildford 4 or Birmingham 6. However, these cases represent the tip of the iceberg and miscarriages of justice still occur quite frequently. Using data from existing miscarriages of justice is important in identifying problems with evidence evaluation, and in protecting those interacting with the criminal justice system in the future.”

Selin Uyguc, a research assistant who worked on the database, described its importance in contextualising problems in the legal system: “Working on this database put me at the heart of some of the stories of those who the law has deeply wronged, and brought them to light. The research is not just about facts or numbers, but lives.”

From next year, University of Exeter law students and psychology students will have the opportunity to work in the new lab group as part of their degree programmes. Students will work on research projects with academics in the lab, and will also work on applying research to help the community through casework and / or campaign work. Existing research assistant, Beth Mann, described her experience working on a project modelling guilty plea decision-making: “Working on this research has given me an important insight into the psychological pressures those who enter our criminal justice system face, and the beneficial ways that data can be used to improve legal process. I feel really grateful to be a part of a team working to help those vulnerable to these pressures and to ensure their rights are protected.”

The database and more information about the work being done by the Evidence Based Justice lab can be found here on our website: www.evidencebasedjustice.exeter.ac.uk. Analyses of data in the database will also be published in Issue 5 (2021) of Criminal Law Review. Anyone interested in the work is encouraged to reach out to Dr. Helm directly.