‘The confession tapes’ shed light on the reasoning behind false confessions

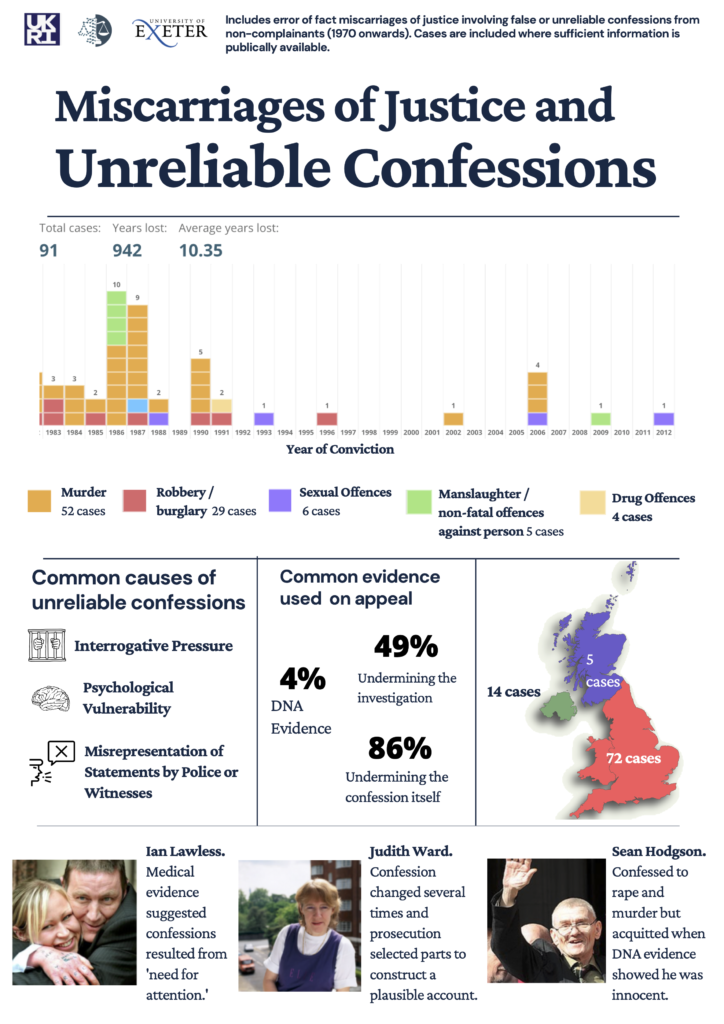

The Netflix documentary series ‘The Confession Tapes’ exhibits the experiences of defendants in multiple US cases in which they have been convicted of crimes they claim they did not commit, but confessed to during police interrogations. This issue is more common in the UK than it may seem at first, with 26.8% of Miscarriages of Justice cases reported in the EBJL UK Miscarriages of Justice Registry classified as having involved a false confession.

The Confession Tapes not only highlights false confessions as a compelling issue within the justice system, but also helps the viewer to understand the circumstances behind why anyone would confess to a crime they did not commit. It is clear from The Confession Tapes that while so many automatically think that ‘I would never confess to something I didn’t do’, it really could happen to anyone, and justice may never be served for those convicted due to confessions they felt they had no choice but to make.

The EBJL Registry contains a false confession ‘wiki’ devoted to discussing the situations in which innocent defendants may confess to crimes they have not committed, and the research that can help inform assessments of whether a confession may be false. Together, the wiki, and The Confession Tapes, highlight three main reasons innocent people confess – custodial and interrogative pressure, psychological vulnerability and lack of transparency surrounding evidence.

Three main reasons why innocent people confess – custodial and interrogative pressure, psychological vulnerability and lack of transparency surrounding evidence.

Custodial and Interrogative Pressure

There are many safeguards in place within both the US and UK to prevent the police from abusing their power in an interview scenario. PACE 1984 governs the UK’s safeguards, giving the accused the right to legal advice and to have a lawyer present in the police interview, providing the right for an appropriate adult to be present should the accused be mentally vulnerable or a juvenile, prohibiting oppressive interviewing, regulating of the length of detention and interview, and ensuring tape recording of police interviews. The US has similar rights derived from the US Constitution, yet both The Confession Tapes suggest police may apply pressure to a defendant with the intention of inducing a confession more regularly than people think. Where this occurs, it is important to consider whether the specific conduct is unlawful or simply against the spirit of the law, particularly in the context of emotional manipulation.

In The Confession Tapes episode titled ‘The Labor Day Murders’, Buddy Woodall is interrogated by police in relation to a double homicide. At first he firmly stated that he was not there nor was he involved in the homicides. There was very little forensic evidence against him, a few hearsay statements from people he knew and some circumstantial evidence concerning his whereabouts when a phone call was made to lure the victims to the scene of the murder, none of which would be likely to convict him. Whilst interrogating Woodall with no lawyer, the police turn on the video camera 10 hours into the interview, where we see them interviewing in an extremely coercive manner, practically hypnotising him, coming up with different scenarios to confuse his memory and emotionally manipulating him into confessing to witnessing the murder. The police tell him multiple times to ‘say it and be done with it’, providing him with only one way out of the tense and distressing environment they have created, and falsely allowing him to believe he will not be punished for what he’d allegedly done if he admitted it (a tactic known as ‘minimisation’). The footage of the interview is disturbing, as it is blatantly clear how the power dynamic of the three policemen compared to one distressed, exhausted suspect is exploited to fit the narrative the police want to create. Although Woodall pleaded not guilty and still maintains that he was coerced into confessing, he remains imprisoned in Georgia for a crime he claims he did not commit, largely due to the confession he made after 10 hours of intensive, suggestive, leading questioning without a lawyer.

This is not an isolated incident to occur, and the EBJL database suggests that similar incidents have occurred in the UK, where a total of 942 years have been lost in the UK justice system due to false confessions, some of them in an eerily similar fashion to Woodall’s case. A well-known example of coerced confessions is The Guildford Four, convicted of murder for blowing up two pubs in Guildford. All four of the accused signed confessions under severe police coercion, perhaps in a more violent manner compared to Woodall’s experience of emotional manipulation, a horrific and unlawful experience achieving the same outcome. There may be somewhat of a stigma around a more emotionally manipulated false confession, as whether it is strictly prohibited under PACE as ‘oppression’ or is simply in bad spirit is a difficult distinction to draw, but The Confession Tapes really draws attention to the power of emotional manipulation and the desperation and damage it can cause.

A less famous UK case relating to this was Stephen McCaul, who was convicted of terrorism-related charges based on a confession made when he was 16. He, like Woodall, was interviewed for an extensive period of time (52 hours) without a lawyer or appropriate adult present, and confessed to the crimes he was accused of. There are plenty of studies suggesting sleep deprivation effects an interviewee’s suggestibility, making them more susceptible to misperceptions or demands, therefore by interviewing for extensive periods of time, police are increasing their chances of achieving a confession, true or not.

The EBJL registry suggests that miscarriages of justice arising as a result of false confessions have reduced dramatically since the early 1990s.

The EBJL registry suggests that miscarriages of justice arising as a result of false confessions have reduced dramatically since the early 1990s. This may be because custodial and interrogative pressure has reduced, or at least become more overt, since PACE. However, continuing to monitor investigative interviewing and continuing to understand how more subtle pressure may produce false confessions will be important to observe. The police v accused dynamic may mean that the problem of false confessions will not go away. The lack of justice at the end of each episode of The Confession Tapes certainly suggests that this is an ongoing problem.

Psychological Vulnerability

Psychological vulnerability can be divided into three different categories when discussing how it may provide susceptibility to false confessions; defendants under 18, defendants with low intelligence or relevant disabilities, and defendants that have a disregard for the truth or a need for attention are all categories of vulnerability. Defendants possessing any of these qualities are highly vulnerable to interrogation situations and their vulnerabilities could make it easier for a false confession to occur, creating a miscarriage of justice.

This plays a huge role in The Confession Tapes episode titled ‘8th and H’, where Clifton Yarborough, a teenager with a low IQ and learning disabilities, was convicted, along with 10 other defendants, of a violent sexual assault and murder due to his confession. In the episode, a video of the end of Yarborough’s police interview shows him recapping his confession robotically, getting many critical details wrong despite being corrected by the police multiple times, alongside an interview of his mother describing his learning difficulties. This is a powerful moment as it is obvious that Yarborough did not understand what he was signing or confessing to and how this was used to the advantage of the police. Defendants with low IQs are more likely to cater to what they think somebody wants to hear, so coupled with the fact Yarborough was a teenager at the time being interviewed with no lawyer or appropriate adult present, there was blatant room for a miscarriage of justice to take place. Yarborough’s confession played a huge role in wrongfully convicting the 10 defendants, who were sentenced to 35 years to life all due to the psychological vulnerability of the defendant that was unfairly utilized by the authorities involved.

There are multiple cases in the UK that mirror Yarborough’s experience, such as Robert Adams, who was 16 when being interviewed for a murder and was denied the support of an appropriate adult, leading to his false confession and subsequently his conviction. Similarly, a group of three men; Colin Lattimore, Ronnie Leighton and Ahmet Salih, all signed false confessions to a murder they did not commit after hours of police interrogation without a lawyer, with 2/3 of them possessing psychological vulnerabilities such as low intelligence and learning difficulties. And these cases aren’t just historic. In 2012 Jack Allen, who suffered from an identity disorder making hum suggestible and compliant, was convicted on the basis of a confession that he made in the early hours of the morning having been refused regular breaks during interviewing. During trial Mr Allen said: “I apologise for lying to the police in the interview but I had to tell them what they wanted to hear; what they told me to say.”

By putting defendants with these vulnerabilities in an interrogation situation and not allowing lawyers or appropriate adults in with them, it is clear to see how a miscarriage of justice could occur, as the lack of understanding and susceptibility to pressure exposes them to the gaps in safeguarding protection that should not exist.

Defendants with a need for attention or disregard for the truth have a slightly different psychological vulnerability in regard to confessions, as they may actively confess rather than reactively, contrastingly to those with vulnerabilities which may cause them to confess as a reaction to the pressure put on them. Cases such as Sean Hodgson and Paul Darvell involve the defendant confessing to murder due to their vulnerabilities. These cases highlight the importance of not simply accepting a confession as true, even when it appears to have been made completely voluntarily. This is important in protecting defendants but also in ensuring that true perpetrators are brought to justice. In Sean Hodgson’s case, DNA evidence recovered at the crime scene eventually showed that he was not guilty, despite initial confessions.

These psychological vulnerabilities raised in both The Confession Tapes and the EBJL certainly help to give insight as to why some people may confess to crimes they didn’t commit, as well as highlighting the necessity to afford greater protection to those who may be more at risk of doing so.

Evidence

The Confession Tapes also shares the importance of evidence as a factor for defendants when confessing to crimes they did not commit. An episode titled ‘A Public Apology’ showed Wesley Myers confessing to killing his girlfriend and setting her alight after being lied to about evidence that allegedly connected him to the scene. The police conducting the interview told him that a hair found on the scene was traced back to him, fabricated that bloody prints were found on his clothes and in his truck, and lied and told him they had an eyewitness placing him at the scene of the crime. This was all untrue, but eventually they convinced him that he had blacked out and committed the murder, leading him to declare ‘if you’ve got all that evidence then I guess I must have done it’. He signed a confession after being interrogated for 15-20 hours over 3 days, apologised in the police station to the victim’s mother, and as he was leaving the station apologised on live TV to the media which the police had called. The small amount of evidence that was not fabricated by the police was forensically unreliable so the majority of the conviction was based upon the confession that was coerced out of Myers by the lies told to him. He was eventually re-tried 16 years later and found not guilty after evidence came back conclusively determining the hair found on the scene was not his. But the damage caused by the duplicity of the police regarding evidence was already done, a significant miscarriage of justice had occured.

Another way evidence can be significant in producing a false confession is using equipment such as a polygraph test or a computer stress testing analyser as investigative tools but implying in interviews they are viewed as scientifically reliable evidence, which is not the case. Karen Boes, in The Confession Tapes episode titled ‘Trial By Fire’ is accused and convicted of killing her daughter by setting fire to her house, which she confessed to. During the 10 hour, lawyer-less interrogation, she was asked to take a polygraph test and agreed, insisting she had nothing to hide but then was told she had failed the test miserably. Although she tried to insist she didn’t know anything about the incident, the polygraph test made her doubt herself, and in a similar defeated manner to Myers, she said ‘I apparently did it according to the test’. The police had also lied and told her they found evidence of gasoline on her clothes, shoes and her fingerprints on the gasoline can, all of which were completely untrue, but contributed to her confession along with the extremely suggestive interviewing she experienced, putting her in a ‘dream-like’ state and coercing her into confessing. The confession led to her conviction, and she is currently still serving life in prison with no possibility of parole, and all appeals have been exhausted. Buddy Woodall, as previously mentioned, was also subjected to a similar test that contributed to his confession- a computer stress testing analyser was used during Woodall’s interrogation and he was similarly told he had failed the test miserably, and believed it may contribute to his conviction if he did not confess.

The Confession Tapes highlights the significance that evidence has when dealing with false confessions, and how the perception of investigative tools has a huge impact on this.

Transparency about the quality and existence of evidence is extremely vital in interrogations in order to create a fair and justiciable system for defendants to choose whether they confess, rather than being forced to when they didn’t even commit the crime. There is much less evidence of this occurring in the UK as polygraph and computer stress testing are not used as ways to aid investigations, but it is highly likely that within the 91 cases of false confession playing a role in the Miscarriages of Justice recorded in the EBJL database, the transparency of evidence has been an issue just as it has within the experiences recorded in The Confession Tapes.

It is clear there are many reasons why someone would confess to a crime they didn’t commit, whether it be due to the intense and coercive nature of interrogations, psychological vulnerabilities that cause a susceptibility to such a pressurised environment or a lack of transparency surrounding the evidence against the accused. All of these are magnified by The Confession Tapes and the EBJL Registry which shows these issues are important in the UK as well as in the US. Analysing these cases provides an answer to the question, ‘Why confess to a crime you didn’t commit?’ and suggests that we should instead be asking how we can better protect defendants given that over 940 total years of freedom have been lost in the UK justice system due to false confessions.

Author Maja Pegler – LLB Law Final Year Student at The University of Exeter & EBJL Database Research Assistant

For more information on false confessions and false memories in real cases in England and Wales see our wiki pages:

https://evidencebasedjustice.exeter.ac.uk/miscarriages-of-justice-registry/the-issues/false-confession/

https://evidencebasedjustice.exeter.ac.uk/miscarriages-of-justice-registry/the-issues/eyewitness-id/

#TheConfessionTapes #EBJL #EvidenceBasedJustice #MiscarriagesOfJustice #FalseConfession