exeter law

Suggestive interviewing, vulnerable suspects, and the Line of Duty Season 6 opener

Suggestive Interviewing, Vulnerable Suspects, and the Line of Duty Season 6 Opener

The first episode of Season 6 of Line of Duty aired on BBC One on 21st March. The series follows investigations of AC-12, a specialist unit investigating police corruption. The first episode was described as returning Line of Duty to what it does best, “dodgy coppers, tense action and characters who communicate almost exclusively in acronyms.” One particularly interesting feature of the episode was the police interview of a suspect with Down syndrome, Terry Boyle (Tommy Jessop), who is arrested on suspicion of murder. The interview was filled with inappropriate questions that would be highly problematic in practice. Although legal regulation (e.g. the Police and Criminal Evidence Act) mean such interviewing would be unlikely to occur in practice, it is still important for suspects and lawyers to recognise potentially problematic questioning. In light of evidence suggesting a ‘CSI’ effect, where the exaggerated portrayal of forensic science and investigation on crime television shows can influence perceptions of the justice system, it is important that fictional shows avoid normalising problematic interviewing techniques.

So, why was the interviewing in line of duty so problematic? First, the interview involved a police officer feeding the suspect details about the case and relevant evidence (e.g., evidence relating to the fingerprints of others found at a crime scene). Giving this type of information to suspects is problematic, since the information can influence the defendants own account by influencing the information that they have about the offence. Where details become known to a suspect during a police interview through exposure to facts about the crime, they come to know this information second-hand. In the example above, a suspect given this information at interview will now have information about the crime scene (e.g., that a specific person was likely to have been at the crime scene). The fact that this information is known by the defendant can come to be seen as incriminating at a later stage of the criminal investigation and trial. This is likely to be particularly important for certain vulnerable defendants who may have a more limited ability to monitor and regulate their memory, and can confuse suggestions with experiences. In court, jurors may be convinced by the fact that the suspect knows facts they could not have known unless they were the true perpetrator, particularly where the suspect does not remember that these facts were given to them by the police.

Lawyers have argued that this type of interviewing led to the alleged false conviction of Brendan Dassey in the United States. They argue that details given by Dassey in his court case did not originate with him but were fed to him during police interviews. For example, they allege that Dassey knew details of the weapon used in an offence as a result of these being fed to him by police.

In Line of Duty this “feeding” of information is combined with the use of leading questions (e.g., did you carry out a thorough cleaning of the property in order to destroy forensic evidence?”). These types of questions can be problematic, particularly with vulnerable defendants, who may have a response bias that leads them to answer “yes” to questions. Some vulnerable groups, including children, do not necessarily have the ability to understand the background knowledge of an interviewer. They may think the interviewer already knows information, and then refrain from going against what they are suggesting even where they do not believe that it is correct.

The fictional interview also shows officers presenting information, including complex forensic information (e.g. relating to gunshot residue) without ensuring understanding of that information or its probative value. Suspects presented with this kind of evidence may end up believing that the police have stronger evidence than they do. This belief can lead them to plead guilty to an offence despite being innocent, or even in some circumstances to come to believe that they actually may have committed an offence that they have not committed. The potential problems with gunshot residue evidence were highlighted in the case of Barry George, who was convicted and then acquitted of murder (https://evidencebasedjustice.exeter.ac.uk/case/barry-george/). Forensic evidence at his initial trial showed a particle of gunshot residue on Mr. George’s coat, but experts later testified that this residue was just as likely to have come from another source as it was to have come from a gun fired by Mr George. Mr George’s conviction was quashed on this basis, but only after he had spent seven years in prison.

In reality, any vulnerable suspect being interviewed would have access to an appropriate adult (https://www.appropriateadult.org.uk/) with the job of safeguarding their interests, entitlement, and welfare. Among other things, appropriate adults can check whether a person understands the meaning and significance of information presented to them, and helping a person to understand the meaning and significance of information and questions.

Ensuring appropriate interviewing is important in both avoiding wrongful convictions and avoiding wrongful acquittals, since once improper interviewing has taken place the value of what might otherwise have been good evidence is compromised. Luckily in practice police uphold high standards in conducting interviews, however it’s still important to remember where mistakes might occur.

For more information on false confessions and false memories in real cases in England and Wales see our wiki pages:

https://evidencebasedjustice.exeter.ac.uk/miscarriages-of-justice-registry/the-issues/false-confession/

https://evidencebasedjustice.exeter.ac.uk/miscarriages-of-justice-registry/the-issues/eyewitness-id/

Database of miscarriages of justice launched as part of new evidence-based justice initiative

Database of miscarriages of justice launched as part of new evidence-based justice initiative

We are really excited to be launching our new site and miscarriages of justice registry today! See below for more information.

A database showing miscarriages of justice that have occurred over the past 50 years has been launched as part of a new initiative aimed at using evidence from psychology and data science to improve the legal system.

The UKRI-funded Laboratory for Evidence-Based Justice, based at the University of Exeter Law School, is a new research group working at the intersection of cognitive psychology, data science, and law. The group’s focus is on better understanding how law and policy interact with human decision-making, for example by examining how law and policy can be used to protect people from pleading guilty when innocent, to enhance evaluations of eyewitness testimony, and to limit the spread of fake news.

Dr. Rebecca Helm, the director of the lab, said: “Data and insight from science have the potential to significantly improve our understanding of how laws and the legal system operate. This understanding is important in protecting those who may be disadvantaged by weaknesses in existing law, and in ensuring the practical effectiveness of law and policy.”

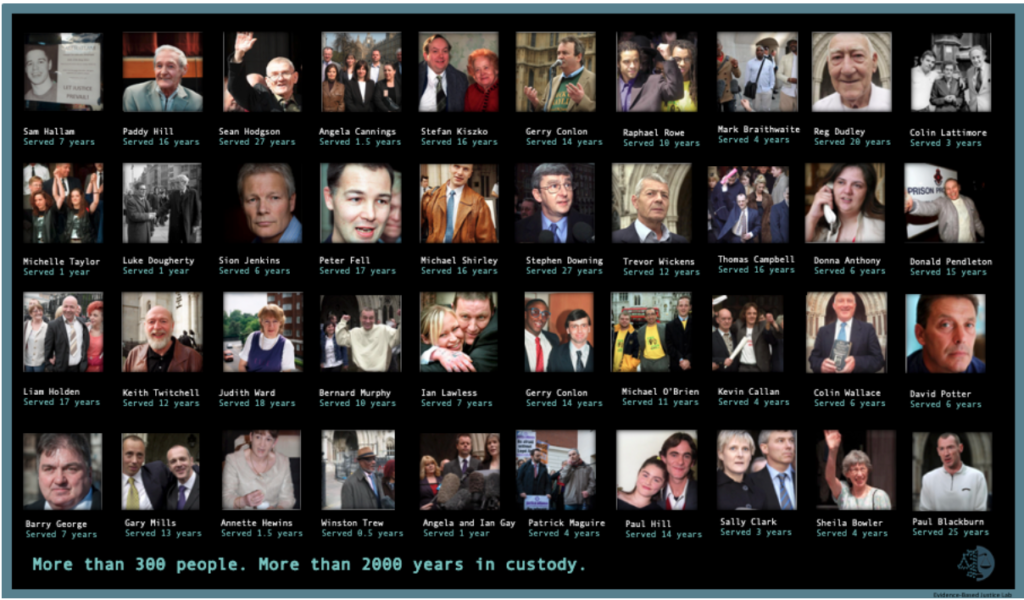

The new database, created by the lab, includes the most comprehensive set of information to date about convictions overturned as a result of factual error in the UK, and covers cases in England and Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland, from 1970 to the present. It currently contains details of 346 cases, classified according to the cause of the miscarriage of justice, the offence involved and the relevant jurisdiction. According to these classifications, one hundred and forty-three (41 per cent) of the miscarriages of justice involved unreliable witness testimony, 91 (26 per cent) involved a false or unreliable confession, 75 (22 per cent) involved false or misleading forensic science, and 73 (21 per cent) involved inadequate disclosure.

The database gives a range of information about each case and includes links to relevant press and legal documentation. It also provides information about key identified causes of miscarriages of justice more generally through online “wikis” that can be added to by researchers, practitioners, and members of the public. The creators hope that the publicly available database will assist in research to improve evidence evaluation and help those who may have been wrongfully convicted themselves.

Dr Helm said: “When people discuss miscarriages of justice in the UK, they often refer to famous cases such as the cases of the Guildford 4 or Birmingham 6. However, these cases represent the tip of the iceberg and miscarriages of justice still occur quite frequently. Using data from existing miscarriages of justice is important in identifying problems with evidence evaluation, and in protecting those interacting with the criminal justice system in the future.”

Selin Uyguc, a research assistant who worked on the database, described its importance in contextualising problems in the legal system: “Working on this database put me at the heart of some of the stories of those who the law has deeply wronged, and brought them to light. The research is not just about facts or numbers, but lives.”

From next year, University of Exeter law students and psychology students will have the opportunity to work in the new lab group as part of their degree programmes. Students will work on research projects with academics in the lab, and will also work on applying research to help the community through casework and / or campaign work. Existing research assistant, Beth Mann, described her experience working on a project modelling guilty plea decision-making: “Working on this research has given me an important insight into the psychological pressures those who enter our criminal justice system face, and the beneficial ways that data can be used to improve legal process. I feel really grateful to be a part of a team working to help those vulnerable to these pressures and to ensure their rights are protected.”

The database and more information about the work being done by the Evidence Based Justice lab can be found here on our website: www.evidencebasedjustice.exeter.ac.uk. Analyses of data in the database will also be published in Issue 5 (2021) of Criminal Law Review. Anyone interested in the work is encouraged to reach out to Dr. Helm directly.