EBJL

Proven Innocent After 11 Years On Death Row: Lessons From The Case of Ron Williamson

Proven Innocent After 11 Years on Death Row: Lessons From The Case of Ron Williamson.

‘In this blog post, our research assistant Carolene discusses the case of Ron Williamson, and what it can teach us about the justice systems in the United States and here in England and Wales‘

John Grisham, a best-selling author and recipient of various accolades, writes fictional books on the most horrific of crimes. From his own imagination, using his legal background as a barrister, he has written numerous legal fiction stories which have caught the attention of many around the world for their horrific nature. For a non-fiction story to have caught his eye, it must have been shocking. To this day, he has only ventured into writing one non-fictional book in his career; when questioned he said that this was such a fundamental miscarriage of justice that he felt the need to share it.

This is the story of Ron Williamson.

Ron Williamson was a successful baseball player- a big name in his small town of Ada. Ada Oklahoma, mid America, is described by Grisham as old fashioned and rural, the sort of American small town you see in the movies. Except this small town had a loud character, and that was Ron Williamson. Disturbing the seemingly peaceful small town, following his failed baseball career due to a shoulder injury, Ron had to move back home to his parents’ house. Suffering from depression he turned to alcohol to cope, and his mental health soon deteriorated. As a result, he became known as a so-called town weirdo, and people called the police on him because he would drunkenly sing along the streets at night or randomly decide to mow people’s lawns without their permission. To many, these are classic signs of someone not coping well mentally. But to the Ada police department these were signs that he may be a horrific murderer and rapist. The link seems so tenuous, because it is. On December 8th, 1982, Debby Carter was murdered and raped when she returned from work after working at a bar. The details of her brutal rape and murder are horrifying, described by the police as the worst they had ever seen. After 5 years of no successful arrests in the murder investigation, the police turned to Ron Williamson.

The best evidence the prosecution could present was a dream that Ron described to the police.

In 1988, along with his drinking buddy Dennis Fritz, Ron Williamson was arrested for the murder. The evidence used to convict him can’t even be called flimsy; it was worse than that. The best evidence the prosecution could present was a dream that Ron described to the police. After being interrogated for days on end and hearing the story all over town, Ron described to the police a dream that he had where he had murdered and strangled Debby. This dream was treated as a confession. To the Ada police the dream seemed sufficient to suggest that Mr Williamson was guilty. In fact, Ada has become infamous for this. In a book by Robert Mayer titled The dreams of Ada, Mayer describes how the small town was so obsessed with securing convictions that several of their convictions were based on “dreams” reported by the defendants. In Grisham’s book he reveals the story of Tommy Ward and Karl Fontenot who were convicted for the murder of a store clerk based on a dream scenario that they described. These men spent 35 years in prison before being released after the State conceded that they were wrongly convicted.

In addition to this poor evidence, there was clear corruption at the heart of Ada’s judicial system. Evidence suggests that the lead prosecutor, Bill Peterson, forced other prisoners to lie and create stories about Mr Williamson. He forced a witness to say that Mr Williamson was at the bar where Debby worked the night of the murder and made a deal with another prisoner, Glen Gore (remember this name for later), to say that Mr Williamson had confessed to the murder whilst waiting for trial, despite Mr Gore being in another part of the prison.

So, the prosecution’s evidence was a dream confession and false witness testimony. Despite this, Ron Williamson was still found guilty at his trial. Since this was Oklahoma, a state which allows the death penalty, Mr Williamson was sentenced to death. However, the death penalty was not the only torture facing him; his increasingly deteriorating mental state was equally as tortuous. Mr Williamson was already suffering from mental health conditions, however being locked up exponentially worsened his mental health problems. Tragically, the state refused to address Mr Williamson’s mental health problems even though he was clearly suffering. He would have episodes of yelling from his cell to then staying in bed for days. One of the prison doctors even recognised the severity of his deterioration and for years requested help, only to be rejected. Where Mr Williamson did receive help, it was minimal and not a sustainable solution. In the US there have been proposed bills to ban the death penalty for mentally ill prisoners, as they are not aware of the situation and consequences (see here). This, however, has been consistently rejected. The State did not seem to care about Mr Williamson or the truth, they focused exclusively on justice for Debby and in doing so tortured an innocent man. Mr Williamson spent 11 years on death row, and at one point was only 5 days off being killed.

Thankfully, the Innocence Project agreed to take on this appeal and with little investigation needed, the lawyers soon realised the absurdity of this case. How could someone be sentenced to death in the absence of any reliable evidence? His lawyer Mark Barrett highlighted the clear issues in the prosecution’s case and Judge Seay ordered a retrial in 1999.

In the late 90s, scientific advances meant that it was possible to accurately identify someone’s DNA when biological material was left at the crime scene. For Ron Williamson, it was crucial in excluding him as the true perpetrator of the crime. The semen found inside Debby Carter did not belong to him and that his DNA was not found at the crime scene. Ron Williamson was finally exonerated on April 15, 1999, after spending 11 years on death row.

Ron was the 78th inmate released from death row since 1973, proving that there are innocent people sent to prison and likely even to their death

This is beyond doubt a massive miscarriage of justice. Ron was the 78th inmate released from death row since 1973, proving that there are innocent people sent to prison and likely even to their death. This is unthinkable, however when we look at this case it is easy to see how failures in investigation led to the wrongful conviction. If those investigating the crime hadn’t been so determined to prove Mr Williamson was guilty then the true offender could have been found. Especially since the true offender was in front of them the whole time.

After further DNA tests, it was revealed that the semen inside Debby Carter belonged to Glen Gore. The prisoner who the prosecution colluded with to be a witness against Mr Williamson.

Mr Williamson’s case is clearly a devastating miscarriage of justice. It can also teach us an important lesson about juror decisions in criminal cases: under the right conditions jurors may find defendants guilty “beyond reasonable doubt” even on the basis of relatively tenuous evidence. This reality may be particularly true in cases like Mr Williamson’s, where all involved are likely to be desperate to obtain justice for the victim. So, what are the implications of this for the justice system?

1. The death penalty should never be an available sentence.

The fact that defendants risk being convicted on relatively little evidence means that while the death penalty is legal there will always be a risk that defendants who are innocent will be executed. This conclusion is supported by empirical research into the death penalty.

In the US 136 prisoners have been released from death row since 1976, some of whom it is now clear are innocent. One recent academic study used statistical analyses and available data to suggest that at least 4.1% of death sentences in the US are likely to be being imposed on innocent people (see here). This highlights a serious risk that the death penalty is being used on innocent people. If the death penalty was the sentence given to Mr Williamson, it can clearly be handed down in cases where the evidence against a defendant is far from overwhelming. And not all defendants will have the ability to later demonstrate their innocence through DNA testing.

Whilst we cannot be sure whether those who have already been executed are innocent, there are several cases which would indicate that this is certainly the case. For example, Ruben Cantu was executed in 1993 after being convicted of murder during an attempted robbery. Tragically, after his execution the key witnesses in the case came forward saying they felt pressured and afraid of the authorities and did not accurately tell the truth. Additionally, Cantu’s co-defendant signed a sworn confession that Cantu was not with him on the night of the crime, thus resulting in the district prosecution himself admitting the death penalty should not have been sought. Luckily for Ron Williamson, he was saved from the death penalty – though only by five days. From this case alone, it is clear that we must question just how many innocent people have been wrongly executed. The Netflix series Innocent man, which is based on Mr Williamson’s story as well as the series The Innocence Files highlight the failures within the judicial system. Given these failures it is hard to see how anyone could advocate for the death penalty even with safeguards. Safeguards clearly do not always work.

2. Further regulation of witness testimony from certain categories of defendant may be necessary.

Mr Williamson’s case shows how several pieces of unreliable evidence may be very convincing to a jury, and may even convince them that a defendant is guilty beyond reasonable doubt. It also adds to research showing that jurors are likely to have difficulty detecting deception in witness testimony.

Evidence from jailhouse informants or others ‘co-operating’ with the police is important in many cases beyond Mr Williamson’s. In a May 2015 ‘Snitch Watch’, the National Registry for Exonerations in the USA found that eight percent of all exonerees in their Registry (119 of the 1,567 cases) were convicted in part by testimony from jailhouse informants. They found that this kind of testimony was more likely to have contributed to miscarriages of justice in more serious cases.

Evidence from witnesses who may be incentivised to lie is not just problematic in the USA. Our database of miscarriages of justice in the UK contains details of 34 miscarriages of justice involving evidence from police informant’s or co-defendants (see here). For example, Gary Ford was convicted of robbery and burglary in 1996 based largely on the evidence of a man called Karl Chapman, who was later shown to have received inducements to give evidence against him. Adam Joof, Levi Walker, Antonio Christie, Michael Osbourne, and Owen Crooks were all convicted of murder largely on the basis of the testimony of a co-defendant who claimed to have witnessed the shooting. Their convictions were overturned on appeal when undisclosed evidence showed that known dishonesty of the co-defendant had not been disclosed to the defence. David Tucker was convicted of robbery based largely on evidence from his co-accused, but was acquitted when evidence showed the co-accused had a clear motive to implicate Mr Tucker regardless of guilt.

This evidence suggests certain types of witness, including jailhouse informants and co-defendants, who are particularly likely to be incentivised to lie. This risk of incentivisation, combined with the difficulties jurors are likely to have in detecting deception, mean that enhanced procedures to protect defendants in these types of case may be necessary. These protections may include enhanced disclosure requirements, or even, in certain cases, excluding evidence from the jury all together based on the risk of an unknown incentive to lie being present. Exclusion of evidence may be particularly appropriate in cases involving jailhouse informants.

Sadly, Ron Williamson died in 2004, at the age of 51, just five years after being exonerated. Thankfully, he was a free man when he died. The lessons learned from his case can be used to help prevent similar injustices being inflicted on other defendants.

For further information on this case, John Grisham’s The Innocent Man book is available online, and a Netflix series named The Innocent Man also tells Mr Williamson’s story.

Author Carolene Clarke EBJL Miscarriages of Justice Student Research Assistant.

#FalseGuiltyPleas #InnocentDeathRow #EBJL #EvidenceBasedJustice #MiscarriagesOfJustice #FalseConfession #CriminalJustice #RonWilliamson #JonGrisham

Can I go back to school now? False confessions and false guilty pleas in children.

‘Can I go back to school now?’ False confessions and false guilty pleas in children.

‘Although reforms may go some way to protect children from falsely confessing, children are still at risk in our criminal justice system which requires them to make decisions capable of impacting the rest of their lives, and subtly pressurises them to make those decisions a certain way.’

In 2019, we watched the re-telling of the infamous Central Park Five wrongful conviction case on Netflix, ‘When They See Us.’ Five school kids were coerced into falsely confessing to a violent rape and assault. Twelve years later they were exonerated when someone else confessed to the crime. But why did they confess if they hadn’t committed the crime? Has this happened in the UK? And are young people still falsely confessing today?

Research shows that false confessions are not as rare as you might think, especially in children.

Children are particularly vulnerable to pressure, coercion, and suggestion, and also lack maturity in judgment. This means that children may falsely confess even under conditions that would not seem coercive to adults. In one well-known false confession case in the UK, Colin Lattimore, Ronnie Leighton and Ahmet Salih, all under 18, falsely confessed to murder after hours of interrogation and without legal advice. They each spent three years in prison as a result of these false confessions until new evidence showed they could not have committed the murder as the prosecution alleged.

Scrutiny of the treatment of the three boys and other notable cases from the mid-1970s, such as the Birmingham Six and Guildford Four cases, helped bring about sweeping legislative changes and the introduction of the 1984 Police and Criminal Evidence Act, commonly known as PACE. The question is, does 1984 PACE provide enough safeguards to account for vulnerabilities? Or is reform needed to protect children?

How effective has PACE been?

A common theme in false confessions in children is the absence of legal representation or legal advice.

The immediate thought to anyone sitting at home watching Netflix would be to question why did the Central Park 5 not ask for legal representation or advice? But like anyone not guilty of a crime, why bother engaging with legal advice if you know for certain you are innocent. A reasonable assumption made by anyone, let alone a child, unaware of the legal repercussions they may soon face. PACE 1984 introduces safeguards to protect all defendants from pressure to falsely confess. For example, detained suspects now all have the right to free legal advice and the right to be represented by a solicitor. There is far less evidence of false confessions in children (and in defendants overall) since the introduction of PACE. However, there is also evidence that the problem has not gone away and that the provision of legal advice is not a panacea for false confession. For example, Oliver Campbell, who was a highly vulnerable 19-year-old when convicted of murder in 1990, said he confessed to the murder because he was “put under pressure” to say things he didn’t want to say, and “felt scared.” He has been identified as highly suggestible, and claims that he had nothing to do with the murder he confessed to.

In addition, it should be noted that the effectiveness of legal representation can vary. Recent work has raised questions about the quality of legal representation in children, particularly in the youth court, and work is being done by both the Solicitors Regulatory Authority and the Bar Standards Board, to improve the quality of legal representation for children.

The reforms brought about by PACE are also unlikely to protect children from feeling pressure to confess in a different way – through pressure placed on them by the legal system to admit guilt. Specifically, children often face compelling pressures and incentives to either admit guilt in exchange for a caution (and avoid prosecution altogether) or to plead guilty in court.

Incentivised false confessions – guilty pleas and cautions.

Children accused of criminal offences often have the opportunity to avoid prosecution, but only if they “admit” involvement in an offence. An admission is required to accept a caution, and is often required by diversion from prosecution schemes. As a result, children face pressure to admit guilt to avoid having proceedings brought against them. These admissions, while not as damaging as a guilty verdict in court, can have important consequences for their futures.

Where they are proceeded against in court, children can sometimes avoid a custodial sentence by pleading guilty where they would risk a custodial sentence if they proceeded to a full trial. These discounts are often thought of as rewarding those willing to admit guilt and take responsibility, but they can be equally viewed as creating a trial penalty, where defendants know that they may effectively be punished for exercising their right to a trial.

These incentives to admit guilt create a system in which young people have to consider a variety of factors other than factual guilt when deciding whether to make an “admission.” Young people might admit guilt to avoid court, to avoid custody, or to avoid a longer sentence, even when innocent. The developmental vulnerabilities discussed above make them particularly vulnerable to doing so.

Dr. Helm’s experimental work supports this idea by suggesting that young suspects are particularly susceptible to pleading guilty when innocent due to their cognitive developmental immaturity. These conclusions are also supported by field work in the US context (see here, for example).

This new form of coercion to admit guilt is more subtle than the pressures outlawed by PACE, but may be equally important, if not more important, in creating miscarriages of justice in children. This is particularly important since vulnerability resulting from relatively low intelligence and cognitive ability may disproportionately disadvantage youth who are at an increased risk of offending due to their socioeconomic status, family structure and wealth. The nexus between violence and poverty can enhance the vulnerability of young suspects and further negatively influence the decision-making process for a young suspect. In a recent paper in the Journal of Law and Society, Dr Helm examines these issues and concludes that children need additional protection in our criminal justice system which is heavily reliant on incentivised admissions.

Conclusion:

So the show is over, and no, Netflix, we do not want to continue watching. The question remains, however, are young suspects, especially suspects who have limited intelligence compared to their peers, adequately protected by the UK legal system?

Young suspects are handicapped by their developmental immaturity, yet the legal system still requires them to make decisions capable of impacting the rest of their lives, and subtly pressurises them to make those decisions a certain way.

While pressure pushes children to make these decisions a certain way, through coercion or incentivisation, children will admit guilt when innocent. More research is currently underway to help and reduce the extent to which innocent children falsely admit guilt. Hopefully, this research can inform policy to ensure that innocent children can comfortably go back to school unharmed and with their future plans intact.

Author Haneet Parhar EBJL Miscarriages of Justice Student Research Assistant.

Follow us on Twitter @ExeterLawSchool @RebeccaKHelm and LinkedIn https://www.linkedin.com/company/evidence-based-justice-lab

For a list of Dr Helm’s academic publications on guilty pleas, see the publications page of our website: https://evidencebasedjustice.exeter.ac.uk/publications/

For more information on our data and research on guilty pleas, see the guilty plea decisions page of our website: https://evidencebasedjustice.exeter.ac.uk/current-research-data/admissions-of-guilt/

For more information on guilty pleas in actual cases in England and Wales, search for guilty plea cases in our miscarriages of justice registry:

https://evidencebasedjustice.exeter.ac.uk/miscarriages-of-justice-registry/the-cases/overview-graph/

#FalseGuiltyPleas #InnocentChildren #EBJL #EvidenceBasedJustice #MiscarriagesOfJustice #FalseConfession #CriminalJustice #CentralParkFive #ColinLattimore #RonnieLeighton #AhmetSalih #PACE1984 #PACE

Suggestive interviewing, vulnerable suspects, and the Line of Duty Season 6 opener

Suggestive Interviewing, Vulnerable Suspects, and the Line of Duty Season 6 Opener

The first episode of Season 6 of Line of Duty aired on BBC One on 21st March. The series follows investigations of AC-12, a specialist unit investigating police corruption. The first episode was described as returning Line of Duty to what it does best, “dodgy coppers, tense action and characters who communicate almost exclusively in acronyms.” One particularly interesting feature of the episode was the police interview of a suspect with Down syndrome, Terry Boyle (Tommy Jessop), who is arrested on suspicion of murder. The interview was filled with inappropriate questions that would be highly problematic in practice. Although legal regulation (e.g. the Police and Criminal Evidence Act) mean such interviewing would be unlikely to occur in practice, it is still important for suspects and lawyers to recognise potentially problematic questioning. In light of evidence suggesting a ‘CSI’ effect, where the exaggerated portrayal of forensic science and investigation on crime television shows can influence perceptions of the justice system, it is important that fictional shows avoid normalising problematic interviewing techniques.

So, why was the interviewing in line of duty so problematic? First, the interview involved a police officer feeding the suspect details about the case and relevant evidence (e.g., evidence relating to the fingerprints of others found at a crime scene). Giving this type of information to suspects is problematic, since the information can influence the defendants own account by influencing the information that they have about the offence. Where details become known to a suspect during a police interview through exposure to facts about the crime, they come to know this information second-hand. In the example above, a suspect given this information at interview will now have information about the crime scene (e.g., that a specific person was likely to have been at the crime scene). The fact that this information is known by the defendant can come to be seen as incriminating at a later stage of the criminal investigation and trial. This is likely to be particularly important for certain vulnerable defendants who may have a more limited ability to monitor and regulate their memory, and can confuse suggestions with experiences. In court, jurors may be convinced by the fact that the suspect knows facts they could not have known unless they were the true perpetrator, particularly where the suspect does not remember that these facts were given to them by the police.

Lawyers have argued that this type of interviewing led to the alleged false conviction of Brendan Dassey in the United States. They argue that details given by Dassey in his court case did not originate with him but were fed to him during police interviews. For example, they allege that Dassey knew details of the weapon used in an offence as a result of these being fed to him by police.

In Line of Duty this “feeding” of information is combined with the use of leading questions (e.g., did you carry out a thorough cleaning of the property in order to destroy forensic evidence?”). These types of questions can be problematic, particularly with vulnerable defendants, who may have a response bias that leads them to answer “yes” to questions. Some vulnerable groups, including children, do not necessarily have the ability to understand the background knowledge of an interviewer. They may think the interviewer already knows information, and then refrain from going against what they are suggesting even where they do not believe that it is correct.

The fictional interview also shows officers presenting information, including complex forensic information (e.g. relating to gunshot residue) without ensuring understanding of that information or its probative value. Suspects presented with this kind of evidence may end up believing that the police have stronger evidence than they do. This belief can lead them to plead guilty to an offence despite being innocent, or even in some circumstances to come to believe that they actually may have committed an offence that they have not committed. The potential problems with gunshot residue evidence were highlighted in the case of Barry George, who was convicted and then acquitted of murder (https://evidencebasedjustice.exeter.ac.uk/case/barry-george/). Forensic evidence at his initial trial showed a particle of gunshot residue on Mr. George’s coat, but experts later testified that this residue was just as likely to have come from another source as it was to have come from a gun fired by Mr George. Mr George’s conviction was quashed on this basis, but only after he had spent seven years in prison.

In reality, any vulnerable suspect being interviewed would have access to an appropriate adult (https://www.appropriateadult.org.uk/) with the job of safeguarding their interests, entitlement, and welfare. Among other things, appropriate adults can check whether a person understands the meaning and significance of information presented to them, and helping a person to understand the meaning and significance of information and questions.

Ensuring appropriate interviewing is important in both avoiding wrongful convictions and avoiding wrongful acquittals, since once improper interviewing has taken place the value of what might otherwise have been good evidence is compromised. Luckily in practice police uphold high standards in conducting interviews, however it’s still important to remember where mistakes might occur.

For more information on false confessions and false memories in real cases in England and Wales see our wiki pages:

https://evidencebasedjustice.exeter.ac.uk/miscarriages-of-justice-registry/the-issues/false-confession/

https://evidencebasedjustice.exeter.ac.uk/miscarriages-of-justice-registry/the-issues/eyewitness-id/

Database of miscarriages of justice launched as part of new evidence-based justice initiative

Database of miscarriages of justice launched as part of new evidence-based justice initiative

We are really excited to be launching our new site and miscarriages of justice registry today! See below for more information.

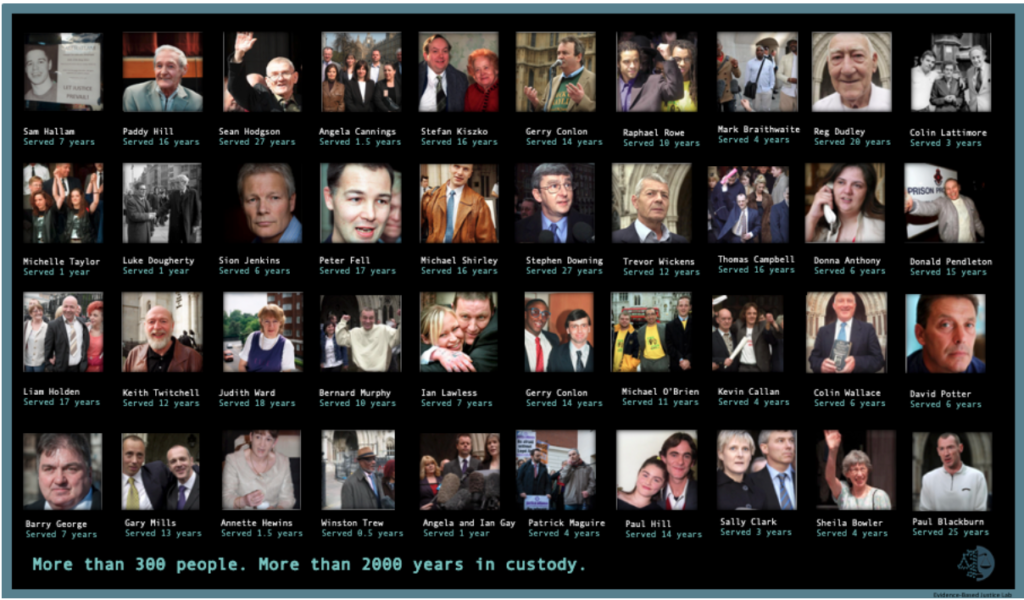

A database showing miscarriages of justice that have occurred over the past 50 years has been launched as part of a new initiative aimed at using evidence from psychology and data science to improve the legal system.

The UKRI-funded Laboratory for Evidence-Based Justice, based at the University of Exeter Law School, is a new research group working at the intersection of cognitive psychology, data science, and law. The group’s focus is on better understanding how law and policy interact with human decision-making, for example by examining how law and policy can be used to protect people from pleading guilty when innocent, to enhance evaluations of eyewitness testimony, and to limit the spread of fake news.

Dr. Rebecca Helm, the director of the lab, said: “Data and insight from science have the potential to significantly improve our understanding of how laws and the legal system operate. This understanding is important in protecting those who may be disadvantaged by weaknesses in existing law, and in ensuring the practical effectiveness of law and policy.”

The new database, created by the lab, includes the most comprehensive set of information to date about convictions overturned as a result of factual error in the UK, and covers cases in England and Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland, from 1970 to the present. It currently contains details of 346 cases, classified according to the cause of the miscarriage of justice, the offence involved and the relevant jurisdiction. According to these classifications, one hundred and forty-three (41 per cent) of the miscarriages of justice involved unreliable witness testimony, 91 (26 per cent) involved a false or unreliable confession, 75 (22 per cent) involved false or misleading forensic science, and 73 (21 per cent) involved inadequate disclosure.

The database gives a range of information about each case and includes links to relevant press and legal documentation. It also provides information about key identified causes of miscarriages of justice more generally through online “wikis” that can be added to by researchers, practitioners, and members of the public. The creators hope that the publicly available database will assist in research to improve evidence evaluation and help those who may have been wrongfully convicted themselves.

Dr Helm said: “When people discuss miscarriages of justice in the UK, they often refer to famous cases such as the cases of the Guildford 4 or Birmingham 6. However, these cases represent the tip of the iceberg and miscarriages of justice still occur quite frequently. Using data from existing miscarriages of justice is important in identifying problems with evidence evaluation, and in protecting those interacting with the criminal justice system in the future.”

Selin Uyguc, a research assistant who worked on the database, described its importance in contextualising problems in the legal system: “Working on this database put me at the heart of some of the stories of those who the law has deeply wronged, and brought them to light. The research is not just about facts or numbers, but lives.”

From next year, University of Exeter law students and psychology students will have the opportunity to work in the new lab group as part of their degree programmes. Students will work on research projects with academics in the lab, and will also work on applying research to help the community through casework and / or campaign work. Existing research assistant, Beth Mann, described her experience working on a project modelling guilty plea decision-making: “Working on this research has given me an important insight into the psychological pressures those who enter our criminal justice system face, and the beneficial ways that data can be used to improve legal process. I feel really grateful to be a part of a team working to help those vulnerable to these pressures and to ensure their rights are protected.”

The database and more information about the work being done by the Evidence Based Justice lab can be found here on our website: www.evidencebasedjustice.exeter.ac.uk. Analyses of data in the database will also be published in Issue 5 (2021) of Criminal Law Review. Anyone interested in the work is encouraged to reach out to Dr. Helm directly.