forensic science

How can psychology maximise the accuracy of forensic science?

How can psychology maximise the accuracy of forensic science?

Emerging research over the last decade has shed light on the risk of error in forensic science. Research from the Evidence-Based Justice Lab at the University of Exeter aims to help tackle this issue by drawing on cognitive psychological research to develop training programmes and selection tools to maximise accuracy and reduce errors in forensic science.

One of these errors can be seen in the case of Shirley McKie: a Scottish police detective accused of leaving her fingerprint at the scene of a murder. Despite denying ever having entered the crime scene, Ms McKie was arrested and charged with perjury. But it was later revealed that the fingerprint examiners originally involved with the case had made a substantial error: the fingerprint at the crime scene never belonged to Ms McKie – who avoided up to eight years in jail on the charges and was later awarded £750,000 in compensation.

So how can these kinds of errors be avoided in the future?

We know that forensic examiners do make errors. Accuracy levels differ between individual decision-makers and between different forensic disciplines – accuracy can range from approximately 90% in some disciplines to only 65% in others. However, these kinds of errors can be reduced by using scientific methods to improve overall professional accuracy. This is generally attempted via training but unfortunately, there is not a lot of published data that shows whether or not this helps. Some research even shows the opposite and suggests that some forensic training programmes don’t generally improve short-term accuracy.

In order to develop effective training programmes to improve accuracy, we need to understand what goes on inside practitioners’ heads when they make accurate decisions. What is it that makes them experts compared to the average person? There are different perceptual and cognitive processes that examiners use when they perform their work – but we don’t yet know much about these. And understanding how examiners make accurate decisions will be crucial to developing programs that could train other practitioners to use these same processes to increase their own accuracy.

So what kind of processes do practitioners use in their work?

My research has shown that examiners use a whole host of different psychological processes. One of these is called featural processing and a practitioners’ ability to break images down into small parts and compare these parts separate to the ‘holistic’ image. For example, a facial examiner who looks at passport images to detect fraud might break down two faces images into separate parts (e.g. eyes, nose, ears, mouth) and then compare these separately between the two images. Breaking the image down into separate pieces can help an examiner take their time and properly look at which parts of the face might look similar or dissimilar in order to help them decide if they are of the same or different people.

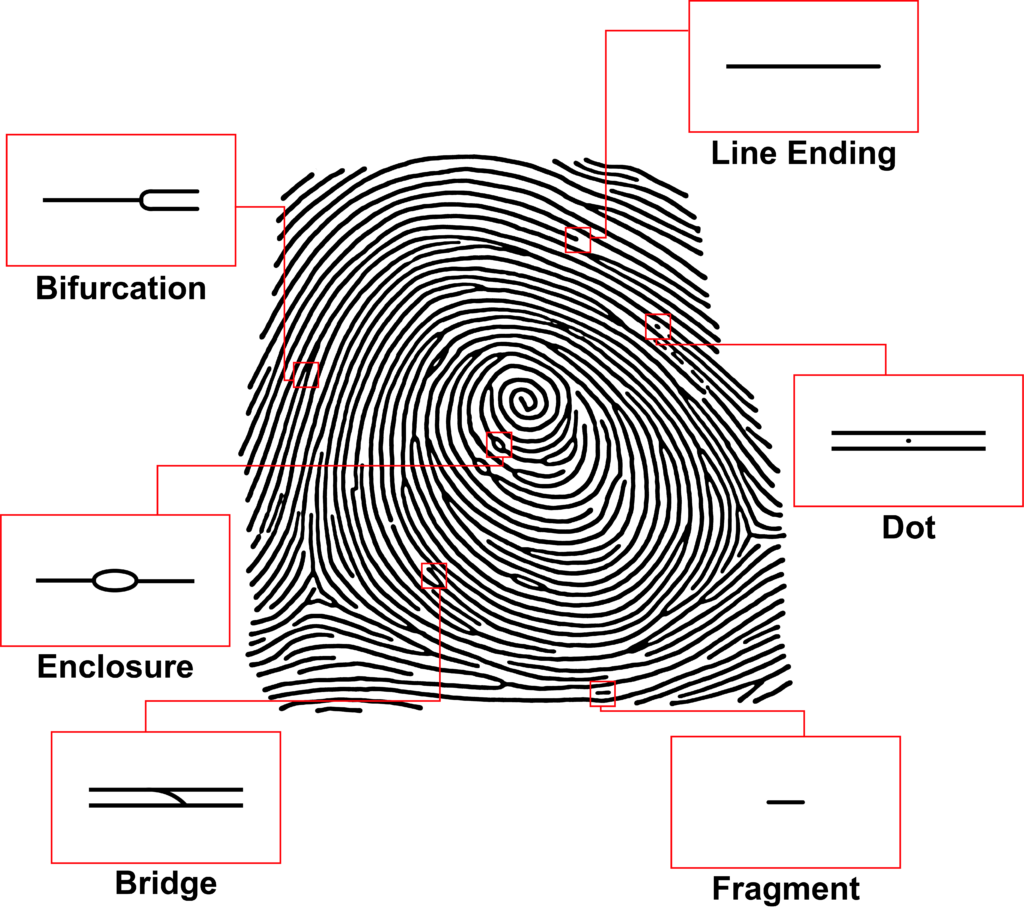

Another process is called statistical learning and is a practitioners’ ability to learn how often features occur in forensic evidence and then use this information to help decide how likely it is two samples are from the same person or different people. For example, fingerprint examiners might learn over some time that certain fingerprint features (e.g. ‘bridges’) are rarer than other fingerprint features (e.g. ‘bifurcations.’). As rarer features are shared between fewer people in the general population, if a fingerprint examiner saw two similar-looking ‘bridges’ in two fingerprints, those two fingerprints would be more likely to be from the same person than if they shared a more common feature.

So where do we go from here?

These are just some of the cognitive and perceptual processes that help examiners in their work. But we must understand more about them in order to develop scientifically-based training programs to improve expert performance. When we understand how practitioners make accurate decisions, we can then use this information to train other practitioners to increase their own accuracy. These training programmes would be even more important for new forensic trainees to help fast-track their expertise. Eventually, this sort of research could even be used to design selection tools to recruit new forensic practitioners on the basis of high-performers on skills we know are important in forensic science.

If you’re interested in learning more about this, please feel free to take part in our latest study run by the University of Exeter and Arizona State University investigating how training could improve performance in fingerprint-matching tasks. We are recruiting fingerprint examiners and anyone else that might want to be in with a chance to win a USD$500 VISA gift-card!

Miscarriages of Justice: Women

Miscarriages of Justice: Women

Identified miscarriages of justice in woman have a different overall profile from those in men.

.Identified miscarriages of justice in woman have a different overall profile from those in men.

Our Miscarriages of Justice Registry suggests that the most common causes of miscarriages of justice in men are false or misleading witness evidence from a non-complainant and false or misleading confessions, but the most common causes of miscarriages of justice in women are inadequate disclosure and false or misleading forensic science.

One striking feature of miscarriages of justice in women is that approximately 25% of the identified cases (13/53) involve women who have been wrongly convicted of harming a child in their care. A similar theme can be seen in the United States National Registry of Exonerations. In a 2014 report, that Registry noted that 40% of female exonerees were exonerated of crimes with child victims. One such case was the case of Sabrina Butler.

Sabrina Butler is a Black American woman, who has survived a tragic miscarriage of justice. In 1990 she was sent to Death Row, later becoming known as the first female to be exonerated; but not before spending 6 years in prison for a crime she did not commit. On April the 12th 1989 when she was just 17, Sabrina’s nine-month-old son died of a hereditary kidney condition. Almost a year later, Sabrina was sentenced to death, falsely accused of taking her own child’s life. Butler has now shared her story, highlighting the pitfalls of the American criminal justice system. From being prevented from attending her baby son’s funeral, to coerced false confessions, she experienced a significant failure of justice.

So, if her son died of a hereditary kidney condition, how did Butler end up being the prime suspect in a murder investigation?

When Sabrina first realised her son was not breathing, she attempted to resuscitate him. Later on, she gave various accounts of what happened, from a fictional babysitter, to jogging with and without the baby. But crucially, she signed a statement confessing that she had punched the baby in the abdomen in response to his consistent crying. This statement was focused on by the prosecution focused upon in her trial. Her defence team called no witnesses, and instead relied on cross-examinations of the prosecution witnesses.

Many reading this may question why on earth an innocent mother would confess to such actions against their own child. But, when reading Butler’s recollections of her interrogation by law enforcement officers, the pressures become clearer;

“I was alone with no lawyer or parent with me. I told him I tried to save my baby. He wrote down what I said and threw it in the garbage. He yelled at me for three hours. No matter what I said, he screamed over and over that I had killed my baby. I was terrified. I was put in jail and not allowed to attend Walter’s funeral.”

“Ambitious men questioned, demoralized and intimidated me. In that state of mind, I signed the lies they wrote on a piece of paper. I signed my name in tiny letters in the margin to show some form of resistance to the power they had over me.”

There has been significant research into why innocent people falsely confess to a crime they did not do. In summary, false confessions most likely occur due to three factors (see here for more information): custodial and interrogative pressure, defendant psychological vulnerabilities (see here for more information) and a lack of transparency regarding evidence. From this list we can clearly see that Sabrina’s case involved at least 2, if not all 3 of these elements. Most concerningly, Sabrina’s accounts describe dangerous levels of police interrogation pressure. Combined with her being a young female and a recent mother who had just lost her baby son, there is no doubt over her psychological vulnerabilities at the time of experiencing this pressure.

Portrayal of a ‘She-Devil’?

Many of the miscarriages of justice involving women do not even involve a false confession. Potentially, women in these situations are susceptible to being judged more harshly and to having unreliable evidence against them more generally interpreted as reliable or even conclusive, due to gender stereotypes.

In a 2019 report, Appeal, a charity fighting miscarriages of justice, have noted the risk that gender-stereotypes play out against women in these types of case (see here). Women who are accused of a crime against a child, especially their own child, are judged negatively and harshly for allegedly violating social stereotypes.

In England and Wales, the majority of miscarriages of justice involving women in cases of this type involve false or misleading forensic evidence. In many cases, this evidence came from a now discredited paediatric pathologist, Dr. Roy Meadow. The below are some examples of women in England and Wales whose stories are detailed in our registry, who were wrongly convicted, and later acquitted, of harming children in their care. Their stories can help us to understand how evidence may be misinterpreted in such cases, how this might lead to miscarriages of justice, and the influence those miscarriages of justice have on victims who are already grieving for the loss of a child.

Sally Clark (see here) – A mother wrongfully convicted of killing her two baby sons, who died just a couple of years apart. She was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1999 but acquitted in 2003 when it was shown that expert evidence presented against her was unreliable. Sadly, Sally struggled to cope after her conviction was overturned and died in 2007.

Angela Cannings (see here) – A mother wrongly convicted of killing two of her three babies who had died as a result of sudden infant death syndrome. She was imprisoned in 2002 but acquitted a year later. She continues to suffer a complicated relationship with her surviving child as a result of her experience.

Suzanne Holdsworth (see here) – A babysitter accused of murdering her neighbours 2-year-old son. She was sentenced to life in prison in 2005 but was found not guilty at a retrial in 2008 when new evidence suggested the child may have died of a seizure.

Donna Anthony (see here) – A mother falsely accused of killing her two babies, convicted in 1998 and acquitted 6 years later when it was shown that expert evidence presented against her was unreliable.

These cases combine devastating circumstances relating to the loss of a child with vulnerable women who are susceptible to judgment and stereotypes prior to their conviction. These are just some of the cases we are now aware of, sadly, it is likely that many have slipped under the radar. As more potential miscarriages of justice, it is important to consider the evidence that is introduced in such cases and how the system can ensure it is effectively scrutinised to an extent that meets relevant scientific standards. By creating an awareness of the problem, we can work with legal and medical professionals to develop solutions.

Author Beth Mann – Graduate Research Assistant

You can read Sabrina’s story first-hand in an article written by her in 2014: https://time.com/2799437/i-spent-more-than-six-years-as-an-innocent-woman-on-death-row/

For our new infographic summarising some of our data on women’s miscarriages of justice see: https://evidencebasedjustice.exeter.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/MiscarriagesofJustice_Women-1.pdf

To search our registry for cases involving women go to the following link, and select “F” for gender: https://evidencebasedjustice.exeter.ac.uk/miscarriages-of-justice-registry/the-cases/overview-graph/