database

Database of miscarriages of justice launched as part of new evidence-based justice initiative

Database of miscarriages of justice launched as part of new evidence-based justice initiative

We are really excited to be launching our new site and miscarriages of justice registry today! See below for more information.

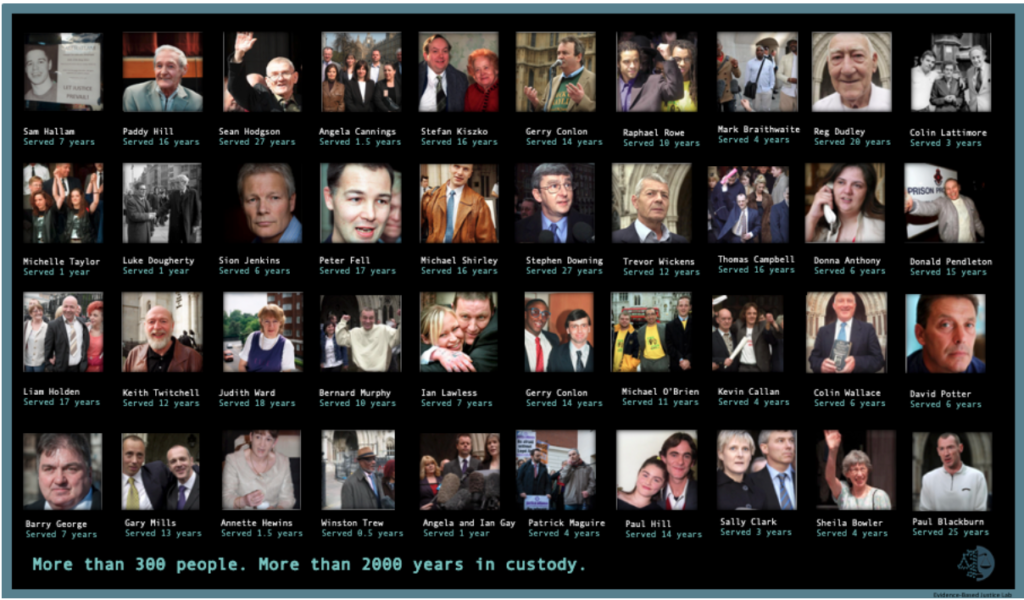

A database showing miscarriages of justice that have occurred over the past 50 years has been launched as part of a new initiative aimed at using evidence from psychology and data science to improve the legal system.

The UKRI-funded Laboratory for Evidence-Based Justice, based at the University of Exeter Law School, is a new research group working at the intersection of cognitive psychology, data science, and law. The group’s focus is on better understanding how law and policy interact with human decision-making, for example by examining how law and policy can be used to protect people from pleading guilty when innocent, to enhance evaluations of eyewitness testimony, and to limit the spread of fake news.

Dr. Rebecca Helm, the director of the lab, said: “Data and insight from science have the potential to significantly improve our understanding of how laws and the legal system operate. This understanding is important in protecting those who may be disadvantaged by weaknesses in existing law, and in ensuring the practical effectiveness of law and policy.”

The new database, created by the lab, includes the most comprehensive set of information to date about convictions overturned as a result of factual error in the UK, and covers cases in England and Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland, from 1970 to the present. It currently contains details of 346 cases, classified according to the cause of the miscarriage of justice, the offence involved and the relevant jurisdiction. According to these classifications, one hundred and forty-three (41 per cent) of the miscarriages of justice involved unreliable witness testimony, 91 (26 per cent) involved a false or unreliable confession, 75 (22 per cent) involved false or misleading forensic science, and 73 (21 per cent) involved inadequate disclosure.

The database gives a range of information about each case and includes links to relevant press and legal documentation. It also provides information about key identified causes of miscarriages of justice more generally through online “wikis” that can be added to by researchers, practitioners, and members of the public. The creators hope that the publicly available database will assist in research to improve evidence evaluation and help those who may have been wrongfully convicted themselves.

Dr Helm said: “When people discuss miscarriages of justice in the UK, they often refer to famous cases such as the cases of the Guildford 4 or Birmingham 6. However, these cases represent the tip of the iceberg and miscarriages of justice still occur quite frequently. Using data from existing miscarriages of justice is important in identifying problems with evidence evaluation, and in protecting those interacting with the criminal justice system in the future.”

Selin Uyguc, a research assistant who worked on the database, described its importance in contextualising problems in the legal system: “Working on this database put me at the heart of some of the stories of those who the law has deeply wronged, and brought them to light. The research is not just about facts or numbers, but lives.”

From next year, University of Exeter law students and psychology students will have the opportunity to work in the new lab group as part of their degree programmes. Students will work on research projects with academics in the lab, and will also work on applying research to help the community through casework and / or campaign work. Existing research assistant, Beth Mann, described her experience working on a project modelling guilty plea decision-making: “Working on this research has given me an important insight into the psychological pressures those who enter our criminal justice system face, and the beneficial ways that data can be used to improve legal process. I feel really grateful to be a part of a team working to help those vulnerable to these pressures and to ensure their rights are protected.”

The database and more information about the work being done by the Evidence Based Justice lab can be found here on our website: www.evidencebasedjustice.exeter.ac.uk. Analyses of data in the database will also be published in Issue 5 (2021) of Criminal Law Review. Anyone interested in the work is encouraged to reach out to Dr. Helm directly.